Volume 49, Issue 1, Spring 2025, Spring 2025

Ready, Set, Coach! An Innovative School Wellness Coaching Program that Helps Get Local School Wellness Policies Off the Shelf and Into Practice

By Catherine A. Wickham, PhD, RDN, CDN, Lynnea Spencer, MEd, RD, LDN, SNS, Nicole Good, Karen McGrail, MEd, RDN, LDN, Denise Courtney, MS, RD, SNS.

Abstract

Identification of the problem

Coaching programs (CPs) in schools often focus on student and teacher wellness, leadership development for teachers and administrators, nutrition and physical activity, and academic achievement. However, there is limited use of CPs for the development and implementation of Local School Wellness Policy (LSWP). The lack of specifically designed CPs for LSWPs may provide a gap that, if filled, will lead to practical and productive solutions.

Actions taken

The Massachusetts School Wellness Coaching Model (MSWCP) was created to provide guided support from School Wellness Coaches for developing and implementing LSWPs. The program is grounded in theory (Transtheoretical Model and Motivational Interviewing), which provides an evidence-based approach to overcoming challenges to the development and implementation of LSWPs, such as time to plan and coordinate and a lack of resources and tools.

Results of actions

Since SY 2020–2021, 51 school districts have enrolled in the MSWCP. Thirty-five school districts completed Tier 1 (an additional nine did not submit their final policy for review), and 22 completed Tier 2 (15 are repeat districts that completed Tier 1). Roughly 12% of the school districts in MA have participated in the program, impacting approximately 18% of enrolled students.

Applications/Impact/next steps

In MA, the MSWCP has been a tremendous success, largely owing to the theory-based framework and the School Wellness Coaches, who remain a steady source of expertise, guidance, support, and encouragement throughout the process. The program has provided students with school environments that nourish their health and well-being. Developing, evaluating, and implementing LSWPs is often a challenge for schools regarding staffing, time, and available resources. The MSWCP has helped fill identified gaps and, in turn, provides a framework to help districts get their LSWPs off the shelf and into practice.

Full Article

Identification of the problem

School Nutrition programs are accountable for Local School Wellness Policies (LSWPs) because the administrative review (Triennial Assessment) includes a check to make sure a policy is in place (United States Department of Agriculture [USDA], 2016). However, having a policy in place does not assure that the policy meets required standards or is actually implemented. While LSWPs must meet the criteria outlined by USDA’s final rule, previous research has shown that only two-thirds of LSWPs meet the required criteria (Moag-Stahlberg et al., 2008). Even when a policy is available, research indicates that only 21% of policies include language to support implementation (Moag-Stahlberg et al., 2008).

In SY 2018–2019, the Massachusetts (MA) Department of Elementary and Secondary Education (DESE) and The John C. Stalker Institute (JSI) of Food and Nutrition at Framingham State University conducted the Massachusetts School Wellness Policy Needs Assessment (MSWNA) to learn what factors acted as barriers or enablers for the implementation of LSWPs (Wickham et al., 2019). Top barriers and enablers revealed that the degree of support and involvement of stakeholders may determine the success of school wellness policy implementation, a concept backed up by previous research by Harriger et al. (2014). Additionally, the MSWNA found that while school nutrition staff are often core enablers of school wellness, they needed assistance in the form of time, tools, resources, and guidance (coaching) to develop and implement wellness-related policies in their schools (Wickham et al., 2019; Wickham et al., 2020). Schools Coaching programs (CPs) in schools often focus on student and teacher wellness (Altunkurek & Bebis, 2019; Lee et al., 2021), leadership development for teachers and administrators (Simkins et al., 2006; Huff et al., 2013), nutrition and physical activity (Li et al., 2019; Tucker et al., 2010), and academic achievement (Kraft et al., 2018; Carver & Orth, 2017; Royer et al., 2019), but there is limited use of CPs for the development and implementation of LSWPs. A study by Hoke et al. (2022) investigated whether a program designed to provide technical assistance in developing school wellness policies could help improve the policy development process and, thereby, policy quality. Additionally, McKee et al. (2023) assessed the impact of school wellness supports, in the form of workshops and coaching sessions, on school wellness-related practices (i.e., nutrition, physical activity, etc.). However, the lack of specifically designed CPs for the development and implementation of LSWPs provides a gap that, if filled, may lead to practical and productive solutions.

Actions taken

Based on the findings from the MSWNA, a CP was developed. The Massachusetts School Wellness Coaching Program (MSWCP) provides guided support for implementing LSWPs. Specifically, it aims to provide districts and, by proxy, school wellness stakeholders “technical assistance with policy compliance, assessment, action planning, implementation, monitoring, and evaluation” (Good & Spencer, 2023).

The Massachusetts School Wellness Coaching Program is theory-based (Transtheoretical Model) and includes motivational interviewing (MI) concepts. The Transtheoretical Model (TTM) was developed by Prochaska and DiClemente (Velicer et al.,1998). TTM is a behavioral theory that is widely used in the healthcare field to achieve behavior change. TTM assesses and motivates individuals through a progression of behavior changes signified by readiness or intention to change. At its essence, the theory focuses on the intention to change behaviors and the change process. It includes a series of steps, including pre-contemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance. When an individual achieves maintenance, the goal is an action plan to maintain the desired behavior (Velicer et al.,1998). Like TTM, MI focuses on achieving behavioral change with a similar element of understanding what motivates someone to change. Additionally, MI features individualized goal setting, developed through open communication between interviewer and interviewee (Miller & Rollnick, 2013; Motivational Interviewing Network of Trainers, 2021).

At the heart of the MSWCP are the School Wellness Coaches (SWCs). SWCs are school nutrition experts and former and current school nutrition professionals who bring a wealth of experience and expertise to the position. SWCs are the backbone of the program, trained in MI and the process of evaluating responses and situations throughout the program. SWCs use a comprehensive coaching manual that provides an overview of the program, including pre/post email templates, sample agendas, meeting coaching guides, coaching prompts, and more. Additionally, SWCs are equipped with training videos and additional readings, ensuring they have all the tools and knowledge needed to succeed.

Throughout the process, SWCs act as facilitators between the School Wellness Chair and the program’s framework, guiding and encouraging participants in developing and implementing their LSWP. SWCs carefully balance their input by urging participants to set the meeting schedule and drive the discussions. Additionally, SWCs strive to foster an environment where participants feel comfortable using the process to continue evaluating and refining LSWPs after the program’s conclusion.

Results of actions

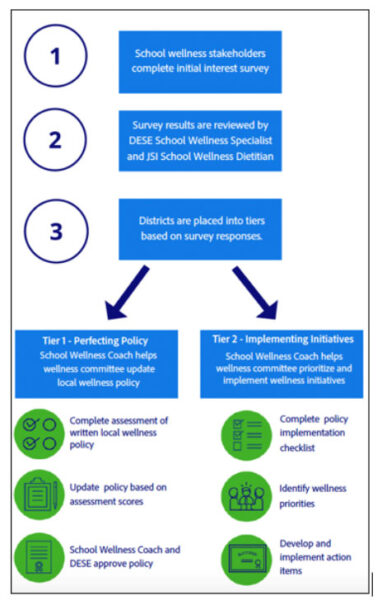

In SY 2020–2021, the MSWCP was piloted with seven MA school districts for feasibility and acceptance. The initial program was focused on a combination of policy and implementation and was designed to move schools from pre-contemplation into action. However, results of the pilot showed that many school wellness policies were outdated and did not meet the USDA’s final rule (e.g., did not, at a minimum, include information such as specific goals, nutrition guidelines for foods/beverages, standards for non-school provided foods consumed in classrooms or used as incentives, food, and beverage marketing, etc.). This finding led to a reevaluation of the program and the development of a two-tiered process, thereby allowing coaching time for the development and evaluation of a school’s current policy (Tier 1) followed by coaching time for the implementation of the policy (Tier 2) (Figure 1).

Upon expressing interest in the program, participants are surveyed to help determine the current state of their LSWP. Surveys are reviewed and scored based on objective and priority (e.g., priority is given to districts that have received a finding on an administrative review) criteria by a DESE School Wellness Specialist and a JSI School Wellness Dietitian. Finally, based on the calculated score, recommendations are made for placement into either Tier 1: Perfecting the Policy or Tier 2: Implementing Initiatives (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Tiered Pathway into School Wellness Coaching Program

For those placed into Tier 1, SWCs assist participants in assessing and updating their school’s LSWP. Participants are coached on how to use the WellSAT 3.0 assessment tool to evaluate their current policy. The WellSAT 3.0 assessment tool is based on best practices and federal requirements within school wellness and helps identify strengths and weaknesses in current policies (Rudd Center, 2021). Upon completing the WellSAT assessment tool, participants receive a scorecard indicating the cohesiveness and strength of the LSWP. In addition to coaching and assistance with WellSAT 3.0, SWCs aid participants with revisions to their policy with an eye toward compliance and facilitate a policy review by a DESE School Wellness Specialist. Finally, SWCs work with participants to submit the revised policy to their School Committee for review, approval, and adoption. Total direct one-on-one SWC time is estimated at six plus hours. An additional four-plus hours is generally needed for an iterative review of the participants’ LSWP and meeting prep. Upon completion of Tier 1, participants may move on to Tier 2 or enter Tier 2 directly after the initial assessment.

In Tier 2, SWCs provide comprehensive support assessing the implementation of LSWP, ensuring participants feel reassured about their efforts. The outcome is a well-structured plan to put LSWPs into action. Participants complete an MA Local Wellness Policy Implementation Evaluation form, select an approach to implement LSWP, and create, execute, and evaluate a plan of action for the LSWP approach. Total direct one-to-one SWC time is estimated at ten plus hours, with an additional eight hours needed for pre/post meeting communications, review of action plans/documents, etc. Since SY 2020–2021, 51 school districts in MA have enrolled in the MSWCP. Thirty-five school districts completed Tier 1 (an additional nine did not submit their final policy for review), and 22 completed Tier 2 (15 are repeat districts that completed Tier 1). Roughly 12% of school districts in MA have participated, impacting approximately 18% of enrolled students. Participating district size ranged from 99–24,000 students, with an estimated 45.5% coming from low-income households (DESE School and District Profiles, 2023). Although Wellness Committees are often made up of many stakeholders, SWCs work directly with School Wellness Committee Coordinators. Coordinators held a variety of school positions, including school nurses (31%), school nutrition directors (17%), administrators and school wellness-related staff (14.5% respectively), health/physical education (13%), and curriculum coordinators/directors (10%).

The MSWCP specifically addresses the need for time, tools, resources, and guidance (coaching), all factors that act as barriers to the development and implementation of LSWPs as identified in the MSWNA (Wickham et al., 2019). While the MSWCP requires an investment of time to complete the program, this time is focused and guided by SWC, which keeps participants on track and motivated. Additionally, the MSWCP is a tool that provides resources and guidance (coaching) to aid with the development and implementation of LSWPs, thereby addressing these specific barriers. For example, after completing the WellStat assessment in Tier 1, the scorecard is reviewed with SWCs who provide assistance in understanding not just the scoring but how participants can move towards special LSWP goals that are clear and well-defined. This takes the burden off participants in having to navigate tools and resources on their own. Finally, funding was identified as a barrier to the development and implementation of LSWP in the MSWNA. Through SY 2023–2024, the costs of the MSWCP were covered by grant or state funds. For SY 2024–2025, program costs were covered by state funding for Tier 1, and Tier 2 participants were charged for SWC time. Districts, in general, may use nonprofit school food service account funds, providing “the local school wellness policy is supporting the operation or improvement of school meal program” (SWITCH, n.d.). The MSWCP filled identified gaps by providing a specifically designed coaching program for developing and implementing LSWPs.

Applications/impact/next steps

Developing and implementing an LSWP that meets or exceeds the USDA final rule standards can be overwhelming. As revealed in the MSWNA, schools need tools and resources to aid the process of developing and implementing LSWPs. The work of the MSWCP, which aims to provide key stakeholders with the support, guidance, and resources needed to develop and implement LSWPs, supports these findings.

The MSWCP has been a tremendous success in MA, with 42 different school districts completing Tier 1 and/or Tier 2. This success is mainly due to the theory-based framework and the SWCs, who remain a steady source of expertise, guidance, support, and encouragement throughout the process. Previous participants have commented:

We participated in both Tier 1 and Tier 2. Our coach brought a wealth of knowledge and expertise that allowed our wellness committee to review/revise our policy as well as create a realistic plan to implement 2–3 goals. This allowed the committee to see real results, which fostered a desire to continue our work. (Participated in Tier 1 & 2.)

The [MSWCP] helped us take our bare-bone, outdated policy and create a working draft that meets all requirements but is also specific to our District. (Participated in Tier 1.)

The [MSWCP] was very valuable to our team. We were provided with just the right amount of guidance to evaluate our school wellness program. Our coach was very knowledgeable and professional. She gave us the tools to succeed and move forward with a solid action plan. (Participated in Tier 2.)

Looking forward to SY 2024–2025, 10 districts have signed up for Tier 1, and another six will enroll in Tier 2 with an expectation that these numbers will increase as the start of the new school year approaches. TTM is a behavioral change theory and, as such, recognizes that the process toward success can be a lengthy journey that may include setbacks. The MSWCP acknowledges this, and outreach has also begun to the nine districts that started Tier 1 but did not submit a final LSWP for evaluation. The outreach is focused on encouraging participants to reenter the program and reminding them of their progress toward their end goal. Of the group that did not complete Tier 1, one district has reenrolled in the program. This is encouraging as the more districts that participate in the MSWCP, the more opportunities for students to experience “…a school environment that promotes student’s health, well-being, and ability to learn” (USDA, FNS, 2024).

The MSWCP is continuing to evolve. For SY 2024–2025, the program will move to a rolling enrollment process, which will provide more opportunities for schools to join the program on their schedule. To meet the demand for the program, a fourth SWC will be hired and trained. Additionally, the MA School Wellness Initiative for Thriving Community Health (SWITCH) has partnered with the Alliance for a Healthier Generation to develop state-specific LSWP assessment tools. The tools will include an LSWP Strength Checklist for Tier 1 assessment and an Implementation Assessment for Tier 2. These tools will replace the use of WellSAT 3.0, and rollout will begin in Spring 2025.

In addition to the direct positive impact of LSWP at schools, MSWCP has provided a model and scaffolding for additional CPs in MA. A testament to this success is the pilot of the Massachusetts School Chef Coaching Program (SCCP) by JSI in SY 2023–2024. This culinary-based program, which pairs a chef with a school nutrition program and provides 12 weeks of chef assistance in culinary-related operational aspects, was highly successful. The SCCP is also grounded in theory (TTM), includes goal setting and one-on-one coaching, and follows a similar framework and process as the MSWCP, further demonstrating the effectiveness of this approach.

The MSWCP is not without limitations, including hiring and retaining qualified SWCs, participant retention, and funding. As the work in LSWP expands, it will necessitate hiring more SWCs; however, the pool of applicants is small due to the expertise required. Therefore, the program may need to continue to adapt to provide potential applicants with advanced training on LSWP. Also, as mentioned previously, continued support and outreach for districts who do not complete the program will be important to help bring all districts in compliance with LSWP requirements. Additionally, while grant and state funding has helped cover program costs in the past, as of SY 2024–2025, Tier 2 participants have been charged for SWC time. While these costs can be covered with school food service account funds, schools must have funds available to participate. Finally, further evaluation will be needed to determine the program’s long-term impact on factors related to the development and implementation of school wellness and student-related outcomes.

Developing, evaluating, and implementing LSWPs is often a challenge for schools regarding staffing, time, and available resources. Future research in this area should seek to further understand best practices that enable districts to develop, evaluate, and implement strong LSWPs. Finally, the study of CPs in LSWP is needed to continue identifying theories and practices that can reduce or eliminate identified barriers. The MSWCP, a theory-based resource that focuses on overcoming challenges to the development, implementation, and evaluation of LSWPs, has helped fill previously identified gaps and, in turn, provides a model to help schools get their LSWP off the shelf and into practice.

References

Agron, P., Berends, V., Ellis, K., & Gonzalez, M. (2010). School wellness policies: Perceptions, barriers, and needs among school leaders and wellness advocates. Journal of School Health, 80(11), 527–535. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2010.00538.x

Altunkurek, S. Z., & Bebis, H. (2019). The effects of wellness coaching on the wellness and health behaviors of early adolescents. Public Health Nursing, 36(4), 488–497. https://doi.org/10.1111/phn.12608

Belansky, E. S., Cutforth, N., Delong, E., Ross, C., Scarbro, S., Gilbert, L., Beatty, B., & Marshall, J. A. (2009). Early impact of the federally mandated local wellness policy on physical activity in rural, low-income elementary schools in Colorado. Journal of Public Health Policy, 30(S1), S141–S160. https://doi.org/10.1057/jphp.2008.50

Carver, L., & Orth, J. (2017). Coaching: Making a difference for k–12 students and teachers. Rowman & Littlefield.

Child Nutrition and Women, Infants, and Children Reauthorization Act of 2004. Pub L No 108–265, June 30, 2004, (118 Sta 729). https://www.congress.gov/108/plaws/publ265/PLAW-108publ265.pdf

DESE. School and District Profiles (2023). https://profiles.doe.mass.edu.

Fernandes, C. F., Schwartz, M. B., Ickovics, J. R., & Basch, C. E. (2019). Educator perspectives: Selected barriers to implementation of school-level nutrition policies. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 51(7), 843–849. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneb.2018.12.011

Food and Nutrition Service [FNS], USDA. (2016). Local School Wellness Policy Implementation Under the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010. Final rule. Federal Register. 81(146), 50,151–50,170. http://www.fns.usda.gov/schoolmeals/fr-072916c

Good, N., & Spencer, L. (2023) Massachusetts School Wellness Coaching Program Manual. Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education Office for Nutrition Programs The John C. Stalker Institute of Food and Nutrition at Framingham State University.

Harriger, D., Lu, W., McKyer, E. L. J., Pruitt, B., Outley, C., Tisone, C., & McWhinney, S. L. (2014). School personnel’s knowledge and perceptions of school wellness policy implementation: A case study. School Nutrition Association, 1–10.

Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act [HHFKA] of 2010, Pub. L. No. 111–296 (2010). https://www.congress.gov/bill/111th-congress/senate-bill/3307

Hoke, A. M., Pattison, K. L., Hivner, E. A., Lehman, E. B., & Kraschnewski, J. L. (2022). The role of technical assistance in school wellness policy enhancement. Journal of School Health, 92(4), 361–367. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.1313

Huff, J., Preston, C., & Goldring, E. (2013). Implementation of a coaching program for school principals: Evaluating coaches’ strategies and the results. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 41(4), 504–526. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143213485467

Kraft, M. A., Blazar, D., & Hogan, D. (2018). The effect of teacher coaching on instruction and achievement: A meta-analysis of the causal evidence. Review of Educational Research, 88(4), 547–588. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654318759268

Lee, J. A., Heberlein, E., Pyle, E., Caughlan, T., Rahaman, D., Sabin, M., & Kaar, J. L. (2021). Evaluation of a resiliency focused health coaching intervention for middle school students: Building resilience for healthy kids program. American Journal of Health Promotion, 35(3), 344–351. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890117120959152

Li, M. H., Sum, R. K. W., Wallhead, T., Ha, A. S. C., Sit, C. H. P., & Li, R. (2019). Influence of perceived physical literacy on coaching efficacy and leadership behavior: A cross-sectional study. J Sports Sci Med, 18(1), 82–90.

Longley, C. H., & Sneed, J. (2009). Effects of federal legislation on wellness policy formation in school districts in the United States. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 109(1), 95–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jada.2008.10.011

Marshall, M. K., The Critical Factors of Coaching Practice Leading to Successful Coaching Outcomes, in Dissertation. 2006. https://aura.antioch.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1688&context=etds

Merrill, R. M., Bowden, D. E., & Aldana, S. G. (2010). Factors associated with attrition and success in a worksite wellness telephonic health coaching program. Education for Health, 23(3), 385.

Miller, W. R., & Rollnick, S. (2013). Motivational interviewing: Helping people change (applications of motivational interviewing). Guilford press.

McKee SL, Xu R, Schwartz MB. Assessing the effects of a statewide training initiative on local school wellness policies. Health Promotion Practice. 2023;24(3):481–490. doi:10.1177/15248399211070808

Moag-Stahlberg, A., Howley, N., & Luscri, L. (2008). A national snapshot of local school wellness policies. Journal of School Health, 78, 562–568. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2008.00344.x

Motivational Interviewing Network of Trainers. (2021). Understanding Motivational Interviewing. https://motivationalinterviewing.org/understanding-motivational-interviewing

Radwan, N. M., Khashan H. A., Alamri, F., & Olemy, A. T. E. (2019). Effectiveness of health coaching on diabetic patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Traditional Medicine Research, 4(6), 314–325.

Rosland, A., Piette, J. D., Trivedi, R., Lee, A., Stoll, S., Youk, A. O., Obrosky, D., Kerr, E. A., & Heisler, M. (2022). Effectiveness of a health coaching intervention for patient-family dyads to improve outcomes among adults with diabetes: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Network Open, 5(11), e2237960. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.37960

Royer, D. J., Lane, K. L., Dunlap, K. D., & Ennis, R. P. (2019). A systematic review of teacher-delivered behavior-specific praise on K–12 student performance. Remedial and Special Education, 40(2), 112–128. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741932517751054

Rudd Center (2021) WellSat: 3.0. Wellness School Assessment Tool. https://www.wellsat.org/default.aspx.

Schuler, B. R., Saksvig, B. I., Nduka, J., Beckerman, S., Jaspers, L., Black, M. M., & Hager, E. R. (2018). Barriers and enablers to the implementation of school wellness policies: An economic perspective. Health Promotion Practice, 19(6), 873–883. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839917752109

Seo, D. (2009). Comparison of school food policies and food preparation practices before and after the local wellness policy among Indiana high schools. American Journal of Health Education, 40(3), 165–173. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ871109.pdf

Simkins, T., Coldwell, M., Caillau, I., Finlayson, H., & Morgan, A. (2006). Coaching as an in‐school leadership development strategy: Experiences from Leading from the Middle. Journal of In-Service Education, 32(3), 321–340. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674580600841901

Siona Decke, S., Hamacher, K., Lang, M., Laub, O., Schwettmann, L., Strobl, R., & Grill, E. (2022). Longitudinal changes of mental health problems in children and adolescents treated in a primary care‑based health‑coaching programme – results of the PrimA‑QuO cohort study. BMC Primary Care, 23(211).

Stanford, M.S., Stiers, M. R., Clinton, T., & Hawkins, R. (2023). Mental health coaching: A faith-based paraprofessional training program. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 26(10), 1007–1020. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674676.2024.2307347

School Wellness Initiative for Thriving Community Health [SWITCH]. (n.d.) Initiatives: Frequently asked questions. https://massschoolwellness.org/initiatives/

Tucker, S., Lanningham-Foster, L., Murphy, J., Losen, G., Orth, K., Voss, J., Aleman, M., & Lohse, C. (2010). A school based community partnership for promoting healthy habits for life. Journal of Community Health, 36(3), 414–422. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-010-9323-9

United States Department of Agriculture [USDA]. (2016). Local School Wellness Policy Implementation Under the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010: Summary of the Final Rule. FNS-627. https://www.asahperd.org/assets/docs/LWPsummary_finalrule.pdf.

United States Department of Agriculture [USDA], Food and Nutrition Service [FNS]. (2024). Local School Wellness Policies. https://www.fns.usda.gov/tn/local-school-wellness-policy.

University of Washington Center for Public Health Nutrition. (2009). Barriers to School Wellness Policy Implementation. https://nutr.uw.edu/wp-content/uploads/2009/11/barriers.pdf.

Velicer, W. F., Prochaska, J. O., Fava, J. L., Norman, G. J., & Redding, C. A. (1998). Detailed overview of the transtheoretical model. Homeostasis, 38, 216–233.

Wickham, C., Crosier, M., & Lehnerd, M. (2019). Massachusetts School Wellness Needs Assessment Final Report. https://johnstalkerinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/MA-School-Wellness-Needs-Assessment-Report-Final.pdf.

Wickham, C. A., Croiser, M., Lehnerd, M., McGrail, K., Courtney, D., & Good, N. (2020). School wellness – It’s everyone’s job! Findings from the Massachusetts school wellness needs assessment. Journal of Child Nutrition & Management, 44(2), n2. https://schoolnutrition.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Findings-From-The-Massachusetts-School-Wellness-Needs-Assessment-Fall2020.pdf

Wolever R. Q., Simmons, L. A., Sforzo, G. A., Dill, D., Kaye, M., Bechard, E. M., Southard, M. E., Kennedy, M., Vosloo, J., & Yang, N. (2013). A systematic review of the literature on health and wellness coaching: Defining a key behavioral intervention in healthcare. Global Advantages in Health and Medicine, 2(4), 38–57. https://doi.org/10.7453/gahmj.2013.042