Volume 39, Issue 1, Spring 2015, Spring 2015

Professional Networks Among Rural School Food Service Directors Implementing the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act

By Disa Lubker Cornish, PhD; Natoshia M. Askelson, MPH, PhD; Elizabeth H. Golembiewski, MPH

Abstract

This study was designed to explore the professional networks of rural school food service directors (FSD), the resources they use for implementing the Healthy, Hunger-free Kids Act of 2010 (HHFKA), and their needs for information and support to continue to implement successfully.

Full Article

The Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010 (HHFKA) mandated many changes related to wellness and nutrition in America’s K-12 schools. Since the HHFKA was passed, school districts across the nation have reported challenges with implementing the new requirements in their kitchens and cafeterias. Much of the media attention has focused on the challenges faced by large and urban school districts rather than those unique to rural districts.

Although obesity and nutritional concerns are issues across the country, rural areas are disproportionately impacted. Children in rural locations are more likely than their urban counterparts to be overweight or obese; poverty and food insecurity are serious concerns in rural areas; and rural adults sometimes perceive themselves to be in so-called “food deserts” with limited food options (Ogden, Carroll, Kit, & Flegal, 2012; Singh, Siahpush, & Kogan, 2010; Singh, Kogan, & van Dyck, 2008; Lutfiyya, Lipsky, Wisdom-Behounek, & Inpanbutr- Martinkus, 2007). Given the limitations of the surrounding food environment, rural K-12 schools are an important source of nutrition for many children. However, food service directors (FSD) in rural districts face particular challenges to successfully implementing HHFKA reforms because of barriers such as limited staffing and lack of proximity to training options and resources.

Professional networks are vital to people in the workplace because networks are the channels through which they can gain access to information and resources (Carrington, Scott, & Wasserman, 2005). Professional networks such as those of health care providers have been studied extensively (Cunningham, et al., 2011). The most recent health care advances can be observed as their adoption moves through a network of health care providers, since new ideas and innovations diffuse through our social and professional networks (Rogers, 1962). For FSD, networks could be an important source for information, resources, and social support. Rural school FSD may benefit from increased opportunities to work with their colleagues in local, regional, and statewide professional networks. Social network analysis is one method to examine formal and informal networks. Formal networks are those that have been superimposed on people, such as their co-workers while informal networks are those that are more fluid and not required (Garbarino, 1981).

In addition, rural FSD may rely on a variety of resources to assist them in their work, but may be in need of additional resources or more efficient and effective means of receiving and accessing the resources. Professional networks may enhance the availability and accessibility of resources for rural FSD and may raise awareness of new resources of which they have not yet taken advantage. To understand more about the resources available to rural FSD, the current study was designed to answer these research questions: 1). What do the professional networks of rural FSD look like? 2). What resources do rural FSD use? 3). What resources do rural FSD still need?

4). Is there administrative and local support for FSD working to implement the HHFKA?

Methodology

The data presented here are part of a larger study related to the challenges and successes experienced by rural school FSD in one Midwestern state while implementing the HHFKA. All research protocols were approved by an Institutional Review Board (IRB) before research activities were initiated. The study relied on concurrent mixed methods and was conducted in Winter 2014. Semi-structured, telephone-based interviews were conducted with rural school FSD, and an online questionnaire was administered to the same population.

Instruments

Open-ended questions that left room for discussion and probing were included in the interview instrument, while closed-ended questions about professional networks and use of specific resources were included in the online survey instrument. This division was intended to reduce the amount of time required of respondents over the phone and to allow respondents flexibility in terms of the nature and timing of their participation. The interview question script and survey were created through a collaborative process with local stakeholders in school nutrition; both were pilot tested by research team members.

Sample

Identification of rural school districts was conducted using rural locale codes of the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES; http://nces.ed.gov/). For the current study, eligible districts included those that were identified by NCES as a “42” (rural, distant) or “43” (rural, remote) locale code (N = 215). Names and contact information of the individuals in each district classified as district FSD were obtained from the state Department of Education. It is important to note that regardless of the title used for these individuals at the district/school level, the Department of Education used the term “food service director” to refer to the people in these positions. FSD in eligible districts were sent an informational letter (N = 215).

Data Collection

All potential participants were invited to complete both the telephone interview and online survey portions of the study. Some individuals elected to complete only one or the other. Participants who wished to take part in the online survey were emailed a unique link to the questionnaire and sent up to two reminder emails.

In the telephone interview, respondents were asked questions regarding knowledge and attitudes of the HHFKA and experiences with its implementation. Trained interviewers probed with additional questions to reach saturation within individual responses. The interviews lasted approximately 20 minutes and were audio recorded for later transcription. The online survey included items about professional responsibilities of the respondents, as well as their training experiences, day-to-day programming operations, and professional networks.

Data Analysis

The survey data were summarized using descriptive statistics, SPSS version 22. Additional participants were not sought because saturation was reached after data collection with the 67 participants was completed. Saturation is frequently used in data collection as an indicator of having a sample size that is large enough; the term refers to experiencing a lack of new themes as additional responses are analyzed (Auerbach & Silverstein, 2003).

Interview analysis, which included close-ended coding of transcripts led to the development of themes and codes based on interview guide content and initial reviews of the interview transcripts. All 67 transcripts were coded by two trained researchers who established inter-coder reliability by coding two randomly selected transcripts and using subjective assessment of coding results (Auerbach & Silverstein, 2003). Finally, a third coder was brought in to review and discuss inconsistencies with the original two coders.

Results And Discussion

Of the 215 potential participants invited via letter, 194 were eligible to participate (14 were non- working numbers and 7 worked in more than one district. Of the 194 eligible potential participants, 12 refused and 115 could not be reached. Six participants elected to complete only the online survey, 16 completed only the telephone interview, and 51 completed both. This resulted in a total of 67 participants for the interview portion (response rate of 35%) and a total of 57 participants for the online survey (for a response rate of 29%).

Survey Data Results

Demographic information and training. The Iowa Department of Education identified all the individuals as “food service directors”, but respondents were asked to self-identify (using as many titles as they felt applied) their title/role and job duties. Respondents reported the following self-identified titles/roles: food service director (43), head cook (16), kitchen manager (6), dietary manager (5), secretary (2), administrator (1), and bookkeeper (1). On average, respondents had worked in the food service industry for 9.2 years. Thirty-three respondents had received some training or education after high school. Such training primarily consisted of opportunities offered by state agencies such as the Cooperative Extension Service. Formal education after high school was not common among those surveyed. Among the online survey participants, 49 worked with vendors and food distributors and including working on budgets and payments. The majority (50 respondents) planned menus themselves and 52 reported supervising staff. The number of staff members supervised ranged from 0 to 25 (M = 7, SD = 5.15).

Professional networks. Respondents were asked to identify (by name and school district) the individuals with whom they communicated regularly for support with HHFKA implementation and daily job responsibilities. Nineteen FSD reported talking to another FSD 1-3 times a month. Only 10 reported never speaking with another FSD, while 23 said they spoke with at least one other FSD less than once a month. Respondents were also asked if they would typically characterize their role in those interactions with other FSD as that of giving advice, seeking advice or both seeking and giving advice (or if it was some “other” reason for communication). Thirty-two FSD responded that they typically both gave and sought advice, while just 2 reported mostly giving advice and 6 reported mostly seeking advice.

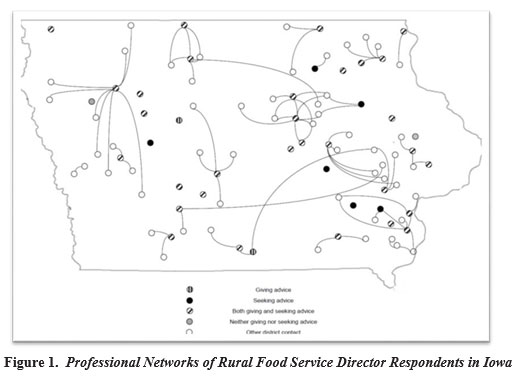

Mapping of online respondent data regarding professional networks revealed that networks tended to be geographically bound; in general, respondents reported speaking with other FSD in districts geographically close to their own (Figure 1). However, some respondents indicated ties with other FSD who were further away, bypassing directors in school districts which were more proximal. There are a few highly connected respondents, but most reported few or no named network ties. Many of the ties reported were to network members that were not included in this study; for example, some of the respondents had ties to network members who were in more urban locations.

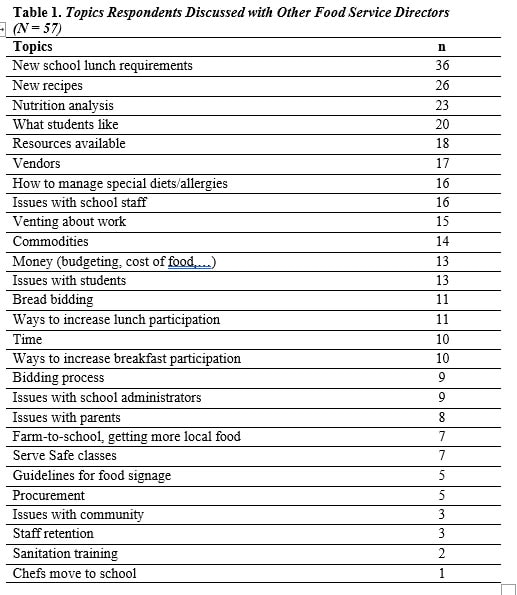

Respondents were asked to identify whether they discussed any listed topics with other FSD and were then asked to identify the single topic they discussed the most (Table 1). The single topic discussed most often was the new school lunch requirements (36 respondents chose this option). Other frequently reported discussion topics included new recipes (n=26), nutrition analysis (n=23), what students like to eat (n=20), and what resources are available (n=18).

Resources used. Respondents to the online survey were asked to identify resources used to implement the HHFKA requirements. Specific response options were provided for possible selection. Survey data (Table 2) revealed that, of the listed resources, the most frequently cited resource used to implement the HHFKA requirements was the state department of education (37), followed by vendor resources (27). The state Team Nutrition group and a consortium or food buying group both were used by more than one-third of respondents to the online questionnaire. When asked specifically about menu planning resources, participants most frequently mentioned online menu planning tools, preexisting menus from other states, or commercially available menus.

Interview Results

Self-identified resources used for HHFKA implementation. In addition to the closed- ended questions from the online survey regarding resources used, interview respondents were also asked open-ended questions regarding the same topic to allow for more breadth or responses. When asked these open-ended questions about resources used to help them implement the HHFKA, respondents most often referred to their communication, contact, and collaboration with other FSD. They did not regularly mention these contacts as “professional networks” per se, but rather as more casual networking opportunities with colleagues, via telephone and in person.

These identified networking opportunities were primarily informal. Respondents frequently cited other FSD, who could share their experiences and strategies for handling challenges, as an important source of information and support. One respondent described this informal use of networks as ‘…a few of us small schools in the area get together every now and then and discuss things that work and things that don’t.’ Another respondent mentioned volunteering in other school districts’ kitchens on her days off to better understand how others do things. Respondents in very small districts reported that sometimes FSD work in multiple districts as a method of sharing resources. Networking allowed these districts to benefit from the knowledge of a director from a larger district.

| Table 2. Resources Used by Rural School Food Service Directors (N = 57) | ||

| Resource | n | |

| Department of Education | 37 | |

| Vendors | 27 | |

| Team Nutrition | 22 | |

| Consortium/food buying group | 20 | |

| Health inspector | 18 | |

| Department of Agriculture/USDA | 16 | |

| School Nutrition Association | 16 | |

| Area Education Agency (regional) | 14 | |

| State consultants for National School Lunch Program | 14 | |

| Dairy Council’s Fuel Up to Play 60 | 6 | |

| Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Program | 5 | |

| Farm to School | 4 | |

| Food Corps | 4 | |

| NE Iowa Food & Fitness (regional) | 2 | |

|

Table 3. Resources Identified as Needs by Rural Food Service Directors |

Theme Example Quotes Staff

More staff/hours needed Probably just extra hands. You know, in the preparation. There’s just two of us so…it gets a little crazy sometimes.

Training Um….well, I would say, well for me, it’s hard to get away. And same with my cooks. They do a lot of different trainings. Sometimes we can’t go cuz if they do it during the school day, we have to get substitutes and then if it’s off school day, then I have to pay them cuz I’m not going to make them go and not pay them so some of it is money too.

Benefits … if we are going to have to start paying out all this money for healthcare, we’re going to have to make the decision, which I know we can’t afford it, we’re going to have to make the decision to ya know, probably the head cook would remain full time, receive the benefits offer, but the other two positions would probably be cut down and have two people do them. Then it would be a split shift probably because we couldn’t afford to pay them the benefits.

Hard to find staff I do, um the only thing I find it is very difficult to find people that want to work for low pay and no benefits…

Help with paperwork I’m happy with what I’m doing if I have just somebody to do the paperwork, and I’ll do the planning of cooking and everything. I’m the person that when it comes to cooking I would rather be the one who is taking care of it because I would like to be sure that the taste, the quality of food is you know, the kids are gonna be really happy when they eat it.

Help with physical part of job

…And of course extra help putting away all the heavy stuff, like grocery and everything….

Skills

Computer skills The tools might be there. I have to admit I am not real good on the computer. I don’t like it and it doesn’t help. I have had uh not such good luck with my computer this year on some things.

Serving Someone to help the staff serve better or give better judgments on what a serving size is. We have spoons that are 2, 3 and 4 ounces and serving spoons and all that. I try to tell them you don’t heap it full and put it on their tray. You level it off but I don’t think they understand what I’m saying.

More staff training Probably more training for my co-workers… I would say they just need, they always come to me for everything and I keep telling them you guys have done this so many times, why can’t you remember what the requirement is. So I think that would be really helpful.

Problem solving help Um I would say more, we used to have a salad bar and we had to get rid of it because we weren’t sure how to make it economically make sense and to be able to serve things that were within the guidelines. I guess that’s one thing that I would like to bring back. Just have more idea of things to serve to get a little bit more variety and then to be able to bring our salad bar back.

Dietitian …a dietitian would be nice, somebody, because you know I cooked for my family and then I just brought it here and I was a fairly healthy eater you know, but it’s a lot stricter now than I’ve ever had.

New ideas Some new ideas, and some different menu ideas, and some kind of training like that would be nice to keep us within the guidelines. Cause I get tired of doing the same old things, I had a variety before but I’m scared that they don’t fit.

Management skills Um… the hardest part for me is maybe the managing part. Just managing the cooks. That is my weakness.

Paperwork Um… probably the support or the education with the paperwork. I came in when all the changes were coming in and I mean it’s so hard. Like they cut down on all, our grocery bill is so high so the expense is high. And then they are like well you got to cut back on your wages because you know you only got a budget of this much. By the time I get in my office I got maybe an hour and it’s like you can’t even have till you start your paperwork because I am not going to get it finished. And so it’s the budgeting that they are asking us to do and not having the support and then yeah they are just ripping us alive here. We are such a small school, you know. And 65% of our kids are free and reduced lunch. So it is pretty hectic here.

Technology

Need upgraded technology

I think it would be nice if they had something that you know, you can just kind of put in with certain brands and whatever and it would just tell you right off the bat that you’re not.

Cost of software I guess there is some kind of a program out there but it’s like expensive. I just found out at a meeting that I went to that there is some kind of a program out there, but… I: But it’s expensive?

Equipment Oh yeah, especially now that we have to do our own condiments, we have to fill little condiment cups because we can only give them one to two ounces and uh, to measure that out we stand with a scooper and put it in these.

There’s got to be a machine out there that would do that

Need new vendors You know I think just um more foods from companies. You know that we keep trying to find new items. And you know there just aren’t that many new items out there that the companies now have made. So I think just were getting ideas and new food. That’s about it.

Commodities Commodities. That is something else. Oh and I have talked to the gals on that I wish that and maybe they are going to try it, but that is such a challenge. You know to have to six times a year get that – I wish it was a lot allocated by once a month. You know and we know ahead of time what was coming more so than just that day for the week. The commodity part has been a challenge. But you know it is what it is.

More networking opportunities

I would like to get together with some area schools and start like a once a month Saturday breakfast where you get together with the heads and talk about the issues you have and how you’ve dealt with them and get some ideas.

Well… maybe a meeting with all the cooks to hear what the other schools are doing more and uh new menu ideas or recipes. Or I guess I feel like I am not real good at the seasonings that the kids really like that we could add to our vegetables and stuff that would make it better.

Money Mmm. The government to give us more money.

More community outreach

I don’t know about support but ya know when someone complains, I guess, cuz I hear it, we’re a small community, I tell them to go, cuz it’s the guidelines, go to the USDA website and see what the guidelines are. So I guess I would like more support to let the community know exactly what the guidelines…exactly why we are doing this. I mean I tell them and I feel like they think I’m just talking.

Menu planning If there was more out there with the menu planning with the new restrictions and stuff. The menu planning is what takes the most time.

Resources still needed. Findings from the interview data suggest several areas identified by respondents as resources they needed or desired (Table 3). The primary themes in this vein of inquiry were: the need for staffing, skills, networking opportunities, technology, equipment, vendors, commodities, money, community outreach, and menu planning assistance. Related to staffing, identified needs included more staff hours, training, benefits, and assistance with responsibilities such as paperwork and the more physically demanding aspects of their jobs. For example, one respondent lamented the difficulty associated with attending trainings: “They do a lot of different trainings. Sometimes we can’t go cuz if they do it during the school day, we have to get substitutes and then if it’s off school day, then I have to pay them cuz I’m not going to make them go and not pay them so some of it is money too.”

Related to additional skills that would be useful, respondents identified computer skills, serving skills, general help with problem solving, new ideas, management skills, better understanding of how to complete paperwork, and additional skills related to dietary considerations. The lack of some skills, such as computer skills, was a barrier to accessing resources for some respondents, as exemplified by this comment: “The tools might be there I have to admit I am not real good on the computer. I don’t like it and it doesn’t help. I have had uh not such good luck with my computer this year on some things.” Other respondents identified the lack of skills as a barrier to implementing the HHFKA requirements as completely as they would like, as exemplified by this comment: “We used to have a salad bar and we had to get rid of it because we weren’t sure how to make it economically make sense and to be able to serve things that were within the guidelines.”

Networking opportunities were identified by respondents as a resource needed to help them implement the HHFKA and execute their job responsibilities. This was mentioned in general terms and also with specific, concrete ideas, such as this comment from one respondent: “I would like to get together with some area schools and start like a once a month Saturday breakfast where you get together with the heads and talk about the issues you have and how you’ve dealt with them and get some ideas.”

Technology and equipment were also identified as needs by respondents. Although many respondents were aware of technological support (such as computer programs or online resources) in theory, they lacked access to those supports for reasons such as financial or knowledge constraints. In addition, respondents noted that the vendor options available to rural districts are more limited than those available to more urban districts. Respondents reported the perception that a more extensive variety of foods would be available to them if a wider array of vendors were serving their rural districts.

Support from administration and community. Interviews included questions regarding perceived support from school administration, teachers, and parents as respondents worked to implement the HHFKA requirements. Responses were mixed regarding all of these groups in terms of both whether support was experienced and the way in which it was offered.

Conclusions And Application

No available previous research has addressed the professional networks of rural school FSD in the context of HHFKA implementation. The results of this mixed methods study show that rural FSD rely on a variety of resources and tools to help them in their daily work. However, the most commonly used resource was their professional network(s). More than any other topic, respondents said that they discussed the new requirements of the HHFKA and how to implement those requirements when they talked with other FSD. This clearly indicates that rural FSD are seeking guidance (and perhaps reassurance, motivation, or inspiration) as they work to implement the HHFKA.

Rural FSD interviewed for this study reported that they both gave and sought advice from other FSD. More frequently, respondents seemed to perceive this communication less as a formal exchange of advice and more as simply discussing issues of concern. Geographically, respondents primarily spoke with other FSD in relatively small geographic areas within the state. Approximately one in five respondents report they never have contact with other rural FSD and one-half have contact just once per month. This suggests that the statewide professional network of rural school FSD is by no means fully realized.

Perceived support varied for respondents and several responses indicated that rural FSD feel isolated when implementing the HHFKA requirements. Many respondents discussed concerns about school meals reforms that have been vocalized between school administrators, teachers and other staff, and parents.

Rural school FSD would benefit from enhanced professional networks that 1) are tailored to their specific needs and constraints, and 2) include conventional and non-conventional stakeholders in child nutrition. Practical solutions can be divided into actions taken at the state and federal levels and those taken at the district and school levels. State and federal efforts should be directed at providing a reliable and efficient infrastructure for networks and initiating the development (and maintenance) of those networks. These networks should be used as a means for disseminating information in a low-cost, sustainable way. When developing professional networks it is important to note that the networks do not have to be constrained by geographic areas, as networks may more naturally be formed by directors who have similar districts as opposed to districts near each other. This would mean that networks could also extend over state boundaries. Broadening networks can also provide directors with access to resources and information that is not available in their local communities.

Additional resources are needed for rural school FSD. However, it is not always clear which resources are needed specifically to implement the HHFKA and which are needed to help struggling rural school kitchens “get by” with general daily operations. HHFKA implementation is more difficult in rural schools than in urban, larger or better-funded school districts. State and federal support should be offered to help smaller, rural districts meet their staffing and equipment needs. In addition, certain entities, such as the state department of education, are strong resources with a track record of providing useful information. These entities should be involved in passing information to networks of FSD.

The resources identified by participants in this study point to ways future information can be provided to FSD. For example, the state department of education will continue to provide useful information and doing so through a formal professional network channel may increase efficiency of message dissemination. Vendors (including local producers) would have the ability to reach many directors more quickly if they communicated through a professional network. Food buying groups or consortia might also be a good starting place for a professional network, as well as sub-groups within the network through which to pass information along. These natural groups could also be used by the state department of education as targets for training or resource allocation.

Many respondents did not explicitly identify professional networks as a formal resource, but remarked that informal conversations with other school food service directors related to job duties and HHFKA implementation were important sources of support and information. Future efforts to connect these directors might consider this finding and structure professional opportunities accordingly—for instance, framing networking events as informal conversation groups rather than tightly prescribed meetings. In addition, direct contact with other food service directors may be fostered in other ways through the elimination of practical or administrative hurdles—such as taking steps to ensure that directors are aware of and have contact information for other directors seeking or looking to give advice, giving directors paid time to make these connections, and facilitating smaller networking activities like kitchen visits or phone calls.

This study is not without limitations. While the rural state used in this study is not unique, it is not clear if particular challenges related to vendors or other geography bound challenges are shared across rural states. This study did not explore the challenges of rural districts in other states. Future research should examine different type of rurality. The study also lacked a direct comparison to matched urban school districts. It is possible that urban districts with FSD who have similar education may face the same type of challenges related to training and education.

This study also has implications for future research. Additional mixed methods research with a larger sample of school FSD that includes urban and rural representation would provide valuable information regarding the differential needs of different types of districts with regard to professional networks. In addition, it may be useful to learn about the perceptions of the potential network stakeholders such as school administrators and vendors, among others. To carefully tailor and develop a more formalized professional network for school FSD that mindfully takes the needs of rural schools into account, it will be critical to gather more detailed information about the needs of the population. In addition, pilot studies will be needed to develop and test the formal professional network infrastructure.

Acknowledgments

This publication journal article was supported by Cooperative Agreement Number 1- U48DP001902-01 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

Auerbach, C. F., & Silverstein, L. B. (2003). Qualitative data: An introduction to coding and analysis. New York: NYU press.

Carrington, P., Scott, J., & Wasserman, S. (Eds.). (2005). Models and methods in social network analysis. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Cunningham, F., Ranmuthugala, G., Plumb, J., Georgiou, A., Westbrook, J., & Braithwaite, J. (2012). Health professional networks as a vector for improving healthcare quality and safety: A systematic review. BMJ Quality and Safety, 21(3), 239-249. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2011-000187

Garbarino, J. (1983). Social support networks: Rx for helping professionals. In J. K Whittaker & J. Garbarino (Eds.) Social support networks: Informal helping in the human services (pp. 3–28). New York: Aldine.

Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010, Pub. L. No. 111-296, §243, 124 Stat. 3183-3266,

Lutfiyya, M., Lipsky, M., Wisdom-Behounek, J., & Inpanbutr-Martinkus, M. (2007). Is rural residency a risk factor for overweight and obesity for U.S. children? Obesity, 15(9), 2348-2356. doi:10.1038/oby.2007.278

Ogden, C., Carroll, M., Kit, B., & Flegal, K. (2012). Prevalence of obesity and trends in body mass index among US children and adolescents. Journal of the American Medical Association, 307(5), 483-490. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.40

Rogers, E. (1962). Diffusion of innovations. New York, NY: Free Press.

Singh, G., Siahpush, M., & Kogan, M. (2010). Rising social inequities in US childhood obesity, 2003- 2007. Annals of Epidemiology, 20(1), 40-52. doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2009.09.008

Singh, G., Kogan, M., & van Dyck, P. (2008). A multilevel analysis of state and regional disparities in childhood and adolescent obesity in the United States. Journal of Community Health, 33(2), 90-102. doi:10.1007/s10900-007-9071-7

Biography

Cornish is an Assistant Professor in the College of Education at the University of Northern Iowa located at Cedar Falls, Iowa. Askelson and Golembiewski are both employed at the University of Iowa in Iowa City, Iowa, where Askelson is an Associate Research Scientist in the College of Public Health and Golembiewski is a Research Assistant in the Public Policy Center.

Purpose / Objectives

Methods

Rural FSD participated in an in-depth telephone interview (n = 67) and an online survey (n = 57). The interview asked respondents about the resources and support they used and still needed to assist with implementing the HHFKA changes, while the online survey focused on professional networks and communication among FSD. The interviews were analyzed by thematic coding, while descriptive statistics were used to summarize survey data.

Results

Respondents reported making extensive use of professional networks by communicating with FSD in other districts. They both sought and gave advice during this communication, and the topic discussed most frequently was implementation of HHFKA requirements. Mapping of network nodes showed that networks of communication were often geographically bound.

Respondents reported using a variety of resources to implement the HHFKA and disclosed that they often relied on their colleagues in other districts for support. Self-identified needs included staffing support, additional networking opportunities, and technology support. Perceived support varied and several responses indicated that rural FSD feel isolated when implementing the HHFKA requirements.

Applications to Child Nutrition Professionals

Rural FSD would benefit from enhanced professional networks that are tailored to their needs and constraints. It may be the case that rural schools need more support overall because existing challenges make HHFKA implementation more difficult than in larger, urban, or better-funded school districts.