Volume 38, Issue 1, Spring 2014, Spring 2014

School Personnel’s Knowledge and Perceptions of School Wellness Policy Implementation: A Case Study

By Diane Harriger, PhD; Wenhua Lu, MA, MS; E. Lisako J. McKyer, PhD, MPH; B. Pruitt, EdD; Corliss Outley, PhD; Christine Tisone, PhD; Sharon L. McWhinney, RD, LD

Abstract

Methods

Thirty-one school personnel from five elementary schools in a school district in Texas were recruited, including fourth grade teachers, physical education (PE) teachers, cafeteria managers, school counselors, school principals, school nurses, an assistant principal, and a life skills coach. Semi-structured interviews were conducted. A thematic content analysis was performed in three steps: coding, thematic categorization, and interpretation. To ensure credibility of findings and interpretations of the data, triangulation and member checking were employed. The school district’s website was also accessed for information and documents about SWP implementation.

Results

Five major themes emerged from examining participants’ knowledge and perceptions of the SWP development and implementation in the school district investigated: (1) belief that more stakeholders should be involved in the policy making and updating processes, (2) awareness that a SWP existed and knowledge that the SWP addressed the school environment, (3) notice of the actual impact of SWP on school environment, (4) perceived impact on child health, and (5) perceived keys to SWP effectiveness.

Application to Child Nutrition Professionals

Results from the this study highlighted the need of improving SWP implementation in three key areas: (1) examining the influence of policy at the local level, (2) clarifying the policy implementation procedures to campus level personnel, and (3) assessing the impact of the policy by accounting for the influence of other policies addressing similar issues.

Full Article

Please note that this study was published before the SY2014-15 implementation of the Smart Snacks Nutrition Standards for Competitive Food in Schools, as required by the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Acts of 2010. As such, certain research relating to food in schools may not be relevant today.

The Child Nutrition and WIC Reauthorization Act of 2004 (Public Law 108-265) included a progressive new provision to address the child obesity epidemic (McDonnell & Probart, 2008). Namely, a mandate outlined a multifaceted approach to improve school environments by increasing opportunities for physical activity and healthy eating and including nutrition education activities (Child Nutrition and WIC Reauthorization Act , 2004; Belansky, Cutforth, Delong, et al., 2009). All local education agencies (i.e. school districts) were required to create and begin implementing School Wellness Policies (SWPs) by the fall of 2006.

By implementing SWPs across the country, policymakers hoped to combat the epidemic of child obesity/overweight by engaging schools, parents, and communities at local levels. Policymakers also expected that local advocates might succeed where national, top down efforts would fail. Each SWP was required to include goals for nutrition education, physical activity, and other school-based activities, as well as nutrition guidelines for all foods available on each school campus. Local educational agencies were also required to establish a plan for measuring implementation of the local SWP and involve parents, students, representatives of the school food authority, the school board, school administrators, and the public in the development of the SWP (Child Nutrition and WIC Reauthorization Act, 2004).

Various studies have been conducted on SWPs since the launch of the mandate, with topics ranging from policy content and compliance with the federal mandate to policy implementation barriers and policy evaluation studies (McDonnell & Probart, 2008). However, most of the studies on SWP implementation were conducted at either state or national levels (Harriger, Lu, McKyer, Pruitt, & Goodson, (in press); Metos & Nanney, 2007; Serrano et al., 2007; Longley & Sneed, 2009; Belansky et al., 2010). There is limited research emphasizing local implementation efforts.

Knowledge of how schools endeavor to craft, communicate and implement the policies is crucial, given that successful policy implementation is more likely to occur when school administration understands campus level personnel’s knowledge, attitudes and perceptions regarding the implementation. Additionally, to understand the perspectives of school district personnel, researchers have employed quantitative methodology or mixed method approaches (McDonnell, Probart, & Weirich, 2006; Molaison & Federico, 2008; Longley & Sneed, 2009; Agron, Berends, Ellis, & Gonzalez, 2010; Belansky et al., 2010). However, the body of research literature presents a paucity of studies that have used only qualitative methodologies to capture the experiences of district employees involved in implementing the SWP. There is a need for qualitative studies, especially case studies, which can provide a holistic, in-depth investigation (Harriger, Lu, McKyer, Pruitt, & Goodson, (in press); Feagin, Orum, & Sjoberg, 1991). Also, the literature has limited examples of applying theory to clarify the policy implementation process. A literature search revealed only two articles that included an explicit theoretical framework to study theory-driven constructs related to SWP implementation (Conklin, Lambert, & Brenner, 2009; Lambert, Monroe, & Wolff, 2010). Utilization of theoretical framework is important for accurate evaluation of policy implementation.

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to describe a school district’s experience of implementing its SWP and examining school personnel’s knowledge and perceptions of the SWP implementation using the organizational model of the Diffusion of Innovations Theory (DOI).

The school district that we investigated was located in Texas, where multiple initiatives were taken to promote a healthy school environment for children before the mandate came into force. The Coordinated Approach to Child Health (CATCH) program, for example, represents a voluntary school-based health program designed to promote physical activity and healthy food choices and prevent tobacco use (Hoelscher et al., 2009). In 2004 the Texas Department of Agriculture (TDA) Food and Nutrition Division (FND) issued the Texas Public School Nutrition Policy (TPSNP) to promote a healthier nutrition environment in schools (Texas Public School Nutrition Policy, 2010). The TPSNP, which is mandatory for all Texas schools participating in USDA child nutrition programs, established specific regulations restricting sale or distribution of foods and beverages of minimal nutritional value to students on campus. Additionally, each independent school system in Texas is required by law to have a School Health Advisory Council (SHAC) which is comprised of (majority) community volunteers and key school and district personnel. The SHACs advise districts on matters related to the coordinated school health program’s local impact.

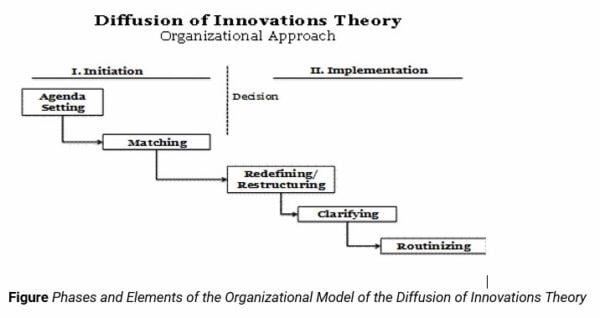

The Diffusion of Innovations Theory (DOI) defines diffusion as “the process in which an innovation is communicated through certain channels over time among the members of a social system” and explains clearly and comprehensively the actions involved in utilizing a new idea (Rogers, 1962). Implementation is the second of two phases outlined by the DOI, which consists of three stages: re-defining, clarifying, and routinizing (Figure). Re-defining/re-structuring occurs when the innovation is re-invented to accommodate the organization’s needs and when the organization’s structure is modified to fit with the innovation (Rogers, 2003). Clarifying is the meaning making process that occurs among organization members as an innovation is utilized (Rogers, 2003). In this stage, members socially construct meaning and common understanding around a new innovation (Meyer & Goes, 1988). Routinizing occurs when an innovation assimilates into an organization’s regular activities (Rogers, 2003).

Methodology

Participant Recruitment

Thirty-one school personnel from five elementary schools in a school district in Texas were recruited, including fourth grade teachers, PE teachers, cafeteria managers, school counselors, school principals, school nurses, an assistant principal, and a life skills coach. There are two primary reasons why elementary schools were chosen for this study. First, previous research has shown that early institution of health behaviors tends to persist whereas behavioral maintenance among adults is extremely difficult. To prevent obesity, therefore, the ideal is to institute and habitualize positive health behaviors early along the developmental spectrum. Second, compared with secondary schools where students change classrooms and instructors frequently and the schedules are intermittent, fewer confounding factors are involved in elementary schools based on how classroom and instruction are delivered.

Researchers initially contacted potential participants by using the email addresses of personnel posted on each school’s website. Snowball sampling methods were then utilized as researchers asked participants to recommend fellow employees who might be interested in participating. Snowballing method was used because it provided a convenient way to identify interconnected potential participants (Check & Schutt, 2011). Prior to data collection, all participants provided written consent to be interviewed and were compensated with a $50 gift card to a local retailer. The Texas A&M University Institutional Review Board approved all study methods and protocols prior to implementation.

Interview Protocol

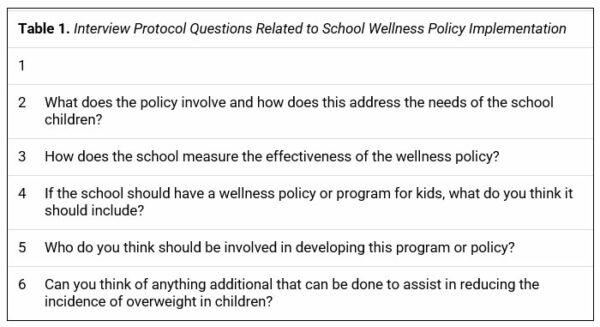

This study was part of a larger study focusing on childhood obesity prevention. The interview protocol was designed to elicit feedback from school personnel on the current state of obesity/overweight among elementary school children. Included in the protocol were questions about SWP as a potential solution to combating childhood obesity (Table 1). The interview questions were developed by the principal investigator (PI) and three co-PIs of whom two are experts in qualitative research methods. The co-PIs also trained the interviewers. The questions were formulated with the research question in mind and informed by the results of focus groups conducted during an earlier phase of this study.

Individual interviews were conducted in the spring of 2009 between trained interviewers and participants at locations chosen by the subjects to foster a sense of security and to protect participants’ identities. Researchers followed a semi-structured interview format. While a set of pre-determined questions served as a general guide, researchers deviated from the guide and probed more thoroughly as needed by engaging participants in open-ended discussions. Each interview was audio recorded and transcribed by the interviewer. The transcripts were verified by a second researcher.

Other Data Sources

Researchers accessed the school district’s website to locate information and documents about SWP implementation such as: the SWP itself, the SWP assessment tool, school board meeting agendas and minutes, and School Health Advisory Council (SHAC) meeting agendas and minutes. Document dates ranged from the fall of 2004 to the spring of 2011. Data from district documents served as factual evidence for the district’s actions in implementing its’ SWP, while interviews accounted for individuals’ experience with the SWP.

Data Analysis

A thematic content analysis of the 31 interview transcripts was performed. In reading interview transcripts, units of coding were first assigned to each independent thought or idea in the text (Green & Thorogood, 2009). A unit of coding is “the most basic segment, or element, of the raw data or information that can be assessed in a meaningful way regarding the phenomenon” (Boyatzis, 1998).

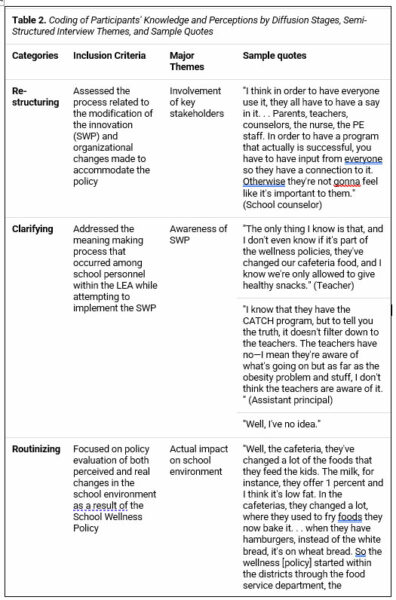

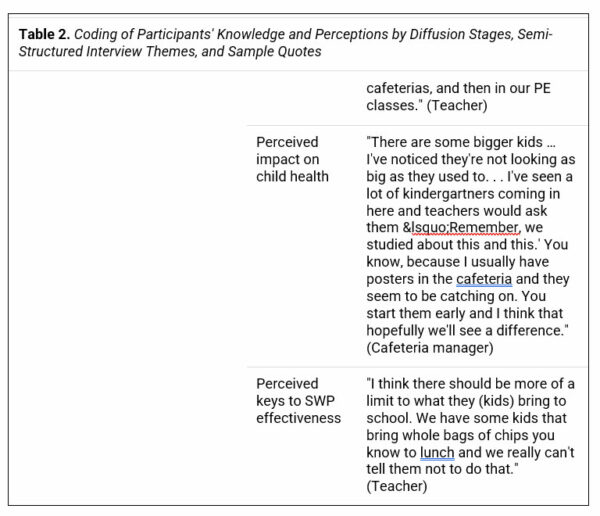

Second, Lincoln’s & Guba’s (Lincoln & Guba, 1985) constant comparative method was employed to sort data units into preliminary groups based on similar characteristics. Thematic groups emerged through a series of iterative steps, allowing the researchers to assign and re-assign coded units to different groups as new data were added (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). For example, the original groups yielded from the units of coding for the first five interview transcripts were shuffled into a random order, combined with units from the next five interviews, and sorted into groups again. The process was repeated 8 times as new data were included. Thematic groups emerged as more data units were categorized. Boyatzis’ (1998) theory-driven code method was then used to develop inclusion/exclusion criteria to group the emergent themes by the three diffusion stage: redefining, clarifying, and routinizing. Groups were assigned to a category based on their fit with the overarching definition of the diffusion stage represented by the category.

Third, based on theory driven code analysis, researchers drew conclusions concerning how the thematic categories related to one another. The interpretation of the thematic categories explained the theoretical framework informing the categorization process (Boyatzis, 1998).

Credibility

To ensure the credibility of factual evidence presented in data units, the researchers verified the data by using multiple data collection methods (interviews, documents, and information on the district website) and multiple data sources (interviews with more than one person and interviews with individuals with different job descriptions) (Lincoln & Guba, 1985; Saldana, 2009). Once the data were categorized thematically, researchers met two local education agency administrators to discuss the thematic categories. Member checking established meaningfulness of findings and accuracy of interpretation (Lincoln & Guba, 1985).

Results And Discussion

SWP Implementation in the Study Area

Davey Independent School District (Davey-ISD)* is located in a rural community in Texas and serves approximately 15,000 students across 25 campuses. Davey-ISD developed both their SWP and evaluation plan the spring before the policy was required to be in place in 2006. In developing their SWP, the School Health Advisory Council (SHAC) of Davey-ISD combined the SWP with policies related to coordinated school health efforts: 1) the Texas Public School Nutrition Policy (TPSNP) (2010), and 2) the statute requiring schools implement a state-approved coordinated school health program. Davey-ISD selected the Coordinated Approach to Child Health (CATCH) to fulfill the SWP mandate, as it included goals for nutrition education and physical activity. The TPSNP meanwhile, includes guidelines for all foods available on campus during the school day (Texas Public School Nutrition Policy, 2010).

Instead of creating a new position, the SHAC recommended that Davey-ISD add the responsibility of ensuring SWP compliance to an existing position, Director of Child Nutrition. By February of 2006, Davey-ISD’s Director of Child Nutrition (Bonnie)* and the Physical Education Director (Jane)* developed a SWP Assessment Tool and presented it to the SHAC. The SHAC voted to accept the Assessment Tool, discussed SWP evaluation procedures and agreed to revisit the SWP each fall to make necessary changes.

In disseminating information throughout the district, Davey-ISD focused on principals and school nurses and trained the nurses to complete the SWP Assessment Tool. The SHAC selected school nurses because they served as point person for health concerns on each campus and were considered dependable to complete the assessment in a timely manner. Regarding implementation of the policy, Bonnie and Jane trained principals at the beginning of each school year on SWP compliance, and emailed updates as necessary throughout the year. In turn, principals relayed policy information and updates along to their employees, e.g., teachers and nurses. Because cafeteria managers communicated directly with Bonnie, she was responsible for managing overall SWP compliance and for the components of the policy specifically related to food service delivery.

Two years after developing its initial SWP and Assessment Tool, Davey-ISD’s SHAC revisited both documents and revised them according to suggestions from central administrators. Because Bonnie and Jane believed the initial assessment of the SWP fell short, they developed more detailed instructions for nurses to supplement the SWP Assessment Tool. The CDC acknowledged Davey-ISD as having an exemplary SWP; a panel of experts in nutrition, physical activity and obesity prevention identified the district as one of only a handful of model districts

Participants’ Knowledge and Perceptions of SWP implementation

Participants’ knowledge and perceptions regarding the development and implementation of the SWP in Davey-ISD were grouped based on the three stages of the implementation phase of the Diffusion of Innovations Theory: re-defining, clarifying, and routinizing (Table 2). Emerging themes are described as follows.

* pseudonym given to protect the anonymity of the school district and participants

Theme 1: Involvement of key stakeholders

Although using the SHAC to develop the SWP met federal requirements, some participants believed additional stakeholders should have been involved in the policy making and policy updating processes. Other participants believed the more people involved in the discussion, the more likely district employees would support the policy. Teacher: “. . . I think they should probably get professional nutritionists involved on their committee or, you know, even educators within the district who are familiar or who have gone to school for that. . . and then even some parents. Because I think if it were a committee and … you know all the stakeholders in there and, being part of it, I think you’d have more buy in.”

School employees commonly perceived that the decision-making process regarding policy development in general (not just the SWP) was too centralized in district administration. Teachers felt they were seldom given an avenue to contribute to the conversation. One teacher voiced her concern, “Everybody should contribute some way, somehow, it’s just a joint effort. . . Everybody has different students, every student is different, and everybody has different opinions. So everybody needs to have a little involvement.”

Theme 2: Awareness of SWP procedures

Communication. Participants acknowledged teacher in-service trainings and educational sessions concerning guidelines for PE requirements and classroom parties. One fourth grade teacher said, “Yes, our coach does always have meetings with us and we are very aware of her. She keeps us very educated on dates and the things that she does.” Another teacher said, “We had a training just in terms of what types of foods we can and cannot have. I mean that’s mandated by the state.” These two quotes are examples of how communication facilitates teacher awareness of SWP procedures.

SWP. Most participants could not articulate the district’s SWP or specific policy requirements; however, many were aware that a SWP existed and knowledgeable that the SWP addressed the school environment (e.g., PE and nutrition requirements). Because the district so closely linked the CATCH program to the SWP, many participants believed the program and the SWP were one and the same. As a result, participants specifically named the CATCH program as the district’s means of addressing child wellness. For example, when asked whether participants were aware of the district’s School Wellness Policy, one teacher replied: “I’m aware that we have one but if you ask me to quote it I would not be able to.” Another teacher said: “Umm, I know there’s a CATCH program that I’ve been to, it’s kind of a cafeteria and PE correlation.”

Most participants knew about a district policy addressing child wellness; however, some expressed concern that information did not always reach the classroom. The assistant principal of one school mentioned that teachers are overwhelmed with preparing for the Texas Assessment of Knowledge and Skills (TAKS) at the end of the year, leaving little room for incorporating additional health related curriculum. The TAKS is a standardized and comprehensive testing program which is used to assess Texas public school students’ attainment of reading, writing, math, science, and social studies skills at grade levels 3-11 (Texas Education Agency, 2012). Almost all participants knew Davey-ISD created a policy to improve students’ health but were not necessarily familiar with the title “School Wellness Policy” and seemed to lump all policy issues into a “government” category.

Policy measurement. Few participants knew the district evaluated the SWP by having campus nurses complete an assessment form. Participants did not know assessment procedures nor mention the health screenings conducted by the nurse twice each school year to assess each child’s health (the evaluation of the CATCH program).

As a whole, participants were aware of the comprehensive nature of the SWP in addressing nutrition education, physical activity and nutrition guidelines. When asked about specifics, participants knew most about the components of the SWP impacting them specifically. For example, classroom teachers were most familiar with the guidelines for classroom parties, PE teachers knew the amount of time children were required to spend on physical activity every week, and cafeteria managers knew the nutritional requirements for school meals.

Theme 3: Actual impact on school environment

At the time of the interviews, the SWP had been in place in Davey-ISD for two and a half years, giving participants time to notice the changes in the school environment and the impact of the changes on children’s health. With the SWP mandate issued by the federal government and additional mandates by Texas, school personnel were conscious of the resulting changes to the school environment.And the changes most commonly mentioned were an increase in PE time and changes in the cafeteria to provide healthier meals.

Theme 4: Perceived impact on child health

Some participants associated the changes in the school environment with a decline in obesity. Since the implementation of the SWP, many participants perceived changes in their students’ health. One teacher mentioned the impact she noticed on her campus. Teacher: “. . . I think it was two years ago … we did have very, very overweight students. We had, I think, 4 or 5 students who were just extremely overweight, but I think that the numbers are decreasing every year. Just because we are making sure that the kids are receiving their required minutes for PE on a weekly basis, and that kids are not standing still outside at recess any more. They are constantly moving. So I think I know it is decreasing.”

Most participants believed the program was making an impact for their students, especially because they perceived that policy requirements were strictest for elementary schools.

Theme 5: Perceived keys to SWP effectiveness

In discussing the long term effectiveness of the SWP in addressing child obesity, many participants believed parental involvement was essential. Bonnie mentioned that if a child eats both breakfast and lunch at school every day of the school year, Davey-ISD is providing only 33% of that child’s meals for the year. If the SWP was intended to combat child obesity, the participants believed joint cooperation with parents and support in the home environment was the key.

One teacher explained her experience in engaging parents of an overweight child in her classroomand the difference it made for her student. Teacher: “. . . we had a student in my class; he had a health problem with his heart and his parents were concerned. The doctor told him that he needed to lose weight. I found out then that you could go to our website and find out exactly what every meal entails: the calories, and all of that. And so that’s even offered to the parents, to say that these are our meals that we feed [the kids] and these are the calories. That little boy lost a substantial amount of weight just from his parents getting that list … He really looks good.”

Davey-ISD administrators attempted to engage parents and increase involvement through parent/child activity nights and other community activities. However, one teacher believed that “they (the district) need to have more education about the lifestyle changes that need to be made here at school and at home. . .” To facilitate lasting change, participants commented that the district also needed to educate parents. Participants also mentioned the importance of school’s role in providing a safe play environment.

Several findings in the current study are in line with findings of previous studies. For example, previous research on SWP has reported strong representation from school administration in developing SWPs (Serrano et al., 2007). Similarly, school employees in the current study commonly perceived that the decision-making process was too centralized in district administration. In a study of schools in lower-income, rural Colorado communities and another national study, participants indicated that competing priorities, e.g., academic achievement, prevented them from increasing students’ time in physical activity or designing curriculum for health and nutrition (Belansky et al., 2009; Agron, 2010). Participants of this study expressed similar concerns that teachers were overwhelmed with preparing for the TAKS and, therefore, didn’t incorporate additional health related curriculum.

Conclusions And Application

This study presented an in-depth analysis of a school district’s experience in implementing its SWP and had several limitations. First, the school district investigated was a local school in Texas, not typical of school districts nationally. Similarly, Texas was not a typical state for implementation of local SWP because of previous state legislation relating to school nutrition programs. Therefore, participants in this study seemed confused as to what changes were due to SWP and which might have been due to CATCH or TPSNP. And there was no way to separate out which changes were due to SWP. Third, the findings represent the perspectives of elementary school personnel, which may not necessarily hold true for personnel at middle and high school campuses given different contexts of the school environment and that state policies are not uniform across all age groups. Despite the limitations, however, insight gained from this school’s experience may inform future inquiry or provide other school districts with suggestions for implementing their SWP.

Results from studying Davey-ISD’s experience with the SWP mandate highlighted findings in three key areas: 1) the influence of policy at the local level, 2) the ambiguity of the policy clarification process, and 3) policy impact.

Influence of Policy at the Local Level

The events and decisions occurring on the district level in Davey-ISD shed light on the overwhelming influence of policy on local school districts. Davey-ISD.’s experience in addressing policies related to the school health environment alone describes the arduous task for district administrators to comply with state and federal mandates. One major difficulty that Davey-ISD experienced in developing its SWP was that before the mandate came into force, several initiatives had been in place to promote a healthy school environment. The school administrators had to make a decision where and how to incorporate the SWP.

A strength of the SWP mandate is its comprehensive nature. By piecing together components of other laws, Davey-ISD developed an overall plan to address child health. Although the district was already complying with state laws addressing several of the individual SWP components, the mandate allowed the district to write a thorough, overarching policy. Having the SWP in place provided a basis of common understanding for administrators, teachers, parents, and community members. Instead of referring to each policy individually, participants believed having one policy in place helped district personnel implement each component consistently across the district.

Ambiguity of the Policy Clarification Process

The clarifying process appears the most difficult of Rogers’ diffusion stages to address. This study and current research on SWP were limited in discussion of the process by which school administrators communicate policy implementation procedures to campus level personnel. In communicating or clarifying new policy to stakeholders, researchers of school health policies, in general, have found a disconnect between “policies as written and policies as practiced” (LeGreco & Canary, 2011). Campus level stakeholders often experienced a conflict between the goals of the policy and local school constraints, e.g., academic pressure or limited funding, which made the clarifying process difficult (Agron, 2010; LeGreco & Canary, 2011). The clarifying process is also challenging to capture given the subtle and casual nature in which one-on-one conversations occur between district employees throughout the school year. Because it is the least overt of the diffusion stages, qualitative research may be the best method for future researchers to better understand the process.

Although district personnel could not recite the SWP verbatim, they were knowledgeable about some of the basic concepts or guidelines of the SWP. Teachers noticed the policy’s influence on the cafeteria, PE time, and food guidelines for the classroom.

Policy Impact

To date only a few studies have analyzed the actual impact of the policy. Considering Davey-ISD’s experience with implementing mandates simultaneously, evaluating the SWP’s impact is difficult. Researchers should take caution in making assumptions about the impact of SWPs without accounting for the influence of other policies addressing similar issues.

In Davey-ISD, changes in the school environment resulted from simultaneous implementation of both state and federal mandates. Traditionally, Texas has been progressive in addressing child health in schools. The TPSNP seemed to have more influence over district decision-making because failing to abide by the mandate resulted in fines for the district. At the time, failing to implement a SWP did not directly result in any penalties. Because other states may not provide such strict requirements, the SWP may be more influential in determining changes to the school environment in other states than in Texas.

In both district documents and subject interviews, Davey-ISD personnel mentioned that parental involvement in conjunction with changes to the school environment was essential for long term success in combating the obesity epidemic. Ultimately, school policies can only go so far in influencing child health behavior. But, although federal and state governments cannot mandate parental involvement, schools can educate both students and parents about healthier eating and exercise habits.

Ultimately, the policymakers’ goal to maintain local and state control while providing a minimum requirement to address child obesity was successful in Davey-ISD. Although changes in the school environment cannot be directly linked to the SWP, the policy did result in administrators creating a formal SWP used as the reference point for wellness guidelines in their district. Davey-ISD.’s experience can help other school districts implement their SWP effectively, thereby improving school health environment.

Acknowledgment

Funding for this project was made possible (in part) by funding from the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities. The views expressed in this manuscript do not necessarily reflect the official policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention by trade names, commercial practices, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

References

Andersen, J.L. (2011). For the sake of health, reflection on the use of social capital and

empowerment in Danish health promotion policies. Social Theory and Health,9, 87-107.

Antonakis, J., Bendahan, S., Jacquart, P., & Lalive, R. (2010). On making causal claims: A review and recommendations. The Leadership Quarterly, 21(6), 1086-1120. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2010.10.010.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory.

Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Costello, R., Loria, C., Lau, J., Sacks, F., & Yetley, E. (2011). Update on nutrition research methodologies: A selective review. Nutrition Today, 46 (3),116-120. doi:10.1097/NT.0b013e318212d4b9

Echon, R.M. (2012). Digital food image analysis: An application of adaptive neural-network

protocols to resolve system (bias) and random errors in nutrient analysis. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 44, (4)S87. doi:10.1016/j.jneb.2012.03.215

Echon, R.M. (2013). Adaptive neural-network protocols for nutrient analysis: Applications of

Learning Vector Quantization and Bayesian methods to resolve bias and random errors. Journal of Food Engineering,116 (1)213-232. doi.org/10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2012.11.013

Fram, M.S., Frongillo, E.A., Jones, S.J., Williams, R.C., Burke, M.P., DeLoach, K.P., & Blake, C.E. (2011). Children are aware of food insecurity and take responsibility for managing food resources. The Journal of Nutrition 141(6),1114-1119. doi:10.3945/jn.110.135988.

Garcia, O., Trevino, R.P., Echon, R.M., Mobley, C., Block, T., Bizzari, A., & Michalek, J. (2012). Improving quality of food frequency questionnaire response in low-income Mexican American children. Health Promotion Practice, 13(6) 763-771. doi:10.1177/1524839911405847

Gold, J., & Shadlen, M. (2007). The neural basis of decision making. Annual Review of

Neuroscience, 30, 535-574. doi:10.1146/annurev.neuro.29.051605.113038

Gundersen, C., Kreider, B., & Pepper, J. (2011). The impact of the National School Lunch Program on child health: A nonparametric bounds analysis. Journal of Econometrics, 166, 79-91.

Hastie, R., & Dawes, R. (2007). Rationale choice in an uncertain world: Psychology of judgment and decision making. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010. Pub. L. No. 111-296, §243, 124 Stat. 3183-3266.

Hearn, S. (2008). Practice based teaching for health policy action and advocacy. Public Health

Reports 123, 65-70.

Hoenselar, R. (2012). Saturated fat and cardiovascular disease: The discrepancy between the scientific literature and dietary advice. Nutrition, 28, 118-123. doi:10.1016/j.nut.2011.08.017

Kraak, V. I., Story, M., & Wartella, E. A. (2012). Government and school progress to promote a healthful diet to American children and adolescents: a comprehensive review of the available evidence. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 42(3), 250-262.doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2011.10.025

Larson, N.I., & Story, M.T. (2011). Food insecurity and weight status among U.S. children and

families: A review of the literature. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 40(2) 166-173.

doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2010.10.028

Lee, J. M., & Lee, H. (2011). Obesity reduction within a generation: the dual roles of prevention and treatment. Obesity, 19(10), 2107-2110. doi:10.1038/oby.2011.199

Mendoza, J., Watson, K., & Cullen, K. (2010). Change in dietary energy density after

implementation of the Texas Public School Nutrition Policy. Journal of the American Dietetic

Association, 110(3) 434-440. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2009.11.021

National Research Council. (2010). School meals: Building blocks for healthy children. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Ogden, C. L., Carrol, M. D., Kit, B. K., & Flegal, K. M. (2012). Prevalence of obesity and trends in body mass index among U.S. children and adolescents, 1999-2010. Journal of the American Medical Association, 307(5)483-490. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.40

Putnam, R. D. (1995). Tuning in, tuning out: The strange disappearance of social capital in

America. Political Science and Politics, 28, 664-83.

Quinn, R., & Rohrbaugh, J. A. (1983). Spatial model of effectiveness criteria: Towards competing values approach to organizational analysis. Management Science, 29, 363-77.

Ree. M., & Earles, C. (1998). In top down decision weighing variables do not matter: A consequence of the Wilk’s theorem. Organizational Research Methods,1, 407-20.

Schein, E.H. (1992). Organizational culture and leadership (2nd ed). San Francisco, CA: Joey-Bass, Inc.

U.S. Department of Agriculture. (2012). Nutrition standards in the National School Lunch and School Breakfast Programs: Final Rule. Federal Register, 7 CFR Parts 210 and 220, 77(17) 4087-4167. Retrieved from

http://www.fns.usda.gov/cnd/governance/legislation/CNR_2010.htm

Wechsler, H., Brenner, N., Kuesler, S., & Miller, C. (2001). Food service and food beverages available at school: Results from the school health policies and programs study 2000. Journal of School Health, 71(7) 313-314.

Wootan, M.G. (2011). Child Nutrition Act Reauthorization, Part 1: Major Highlights of the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010. NASN School Nurse, 26(3) 188-189.

doi:10.1177/1942602X11406286

Zelmann, K. (2011). The great fat debate: A closer look at the controversy – Questioning the validity of age-old dietary guidance.Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 111(5) 655-658. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2011.03.026

Biography

Echon is the lead scientist and engineer for Integrated Neurohealth. He specializes in Adaptive Neural Network (ANN) and is the developer of the School Food Imaging systems used in this study.

Purpose / Objectives

The purpose of this study was to describe a school district’s experience of implementing its School Wellness Policy (SWP) and examine school personnel’s knowledge and perceptions of the SWP implementation.