Volume 36, Issue 1, Spring 2012, Spring 2012

Key Strategies for Improving School Nutrition: A Case Study of Three School Nutrition Program Innovators

By Jennifer M. Sacheck, PhD; Emily H. Morgan, MS, MPH; Parke Wilde, PhD; Timothy Griffin, PhD; Elizabeth Nahar, MSW, MBA; Christina D. Economos, PhD

Abstract

Methods

School districts that had >1,000 students, =3 schools, and =40% of students who qualified for free- or reduced-price lunch were identified in three New England states. The districts were contacted via e-mail and phone to determine if significant positive changes had occurred in their school nutrition system within the past 5 years. Twelve school nutrition programs meeting these criteria were interviewed to determine the extent of their efforts to increase the availability of fresh fruits, vegetables, and whole grains; reduce the availability of processed foods; and participate in a farm-to-school program. Three districts were chosen based on the reports of positive changes, and on district size and state location criteria. Interviews and site visits were conducted to fully examine policies, school nutrition program dynamics, and finances in the three selected districts.

Results

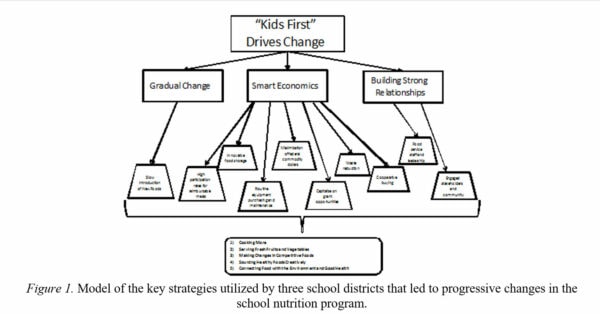

A universal commitment to “kids first” enabled the three school districts to make great strides in the conception and implementation of five common strategies to give children access to healthful meals and reduce the availability of unhealthful foods: 1) cooking more; 2) serving fresh fruits and vegetables; 3) making changes in competitive foods; 4) creatively sourcing healthful foods; and 5) connecting food with the environment and good health. Ultimately, improvements in healthful food had to be either revenue-neutral or, alternatively, increased costs had to be offset by economic savings elsewhere in the school nutrition budget. Building strong relationships among school nutrition staff, school administration, and the community was an important element within all of these strategies.

Application to Child Nutrition Professionals

This case study of three school districts suggests that strong and persistent leadership promoting financial and culinary creativity is critical to school nutrition program success in providing access to healthful foods for students and maintaining fiscal solvency.

Full Article

Please note that this study was published before the implementation of Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010, which went into effect during the 2012-13 school year, and its provision for Smart Snacks Nutrition Standards for Competitive Food in Schools, implemented during the 2014-15 school year. As such, certain research may not be relevant today.

Experts agree that a focus on healthful foods served in school nutrition programs is one component of the child’s environment that may assist in reversing the childhood obesity epidemic. Not only is more nutritious food at school good for children’s health, it has also been documented that eating nutritiously boosts academic performance (Murray, Low, Hollis, Cross, & Davis, 2007). Despite the enormous potential benefits of healthier food choices at school, many communities and school districts find achieving positive change in school nutrition programs to be a formidable challenge. School nutrition programs face tough competing pressures for good nutrition, popular appeal, and economic success. This is referred to as the school food trilemma (Ralston, Newman, Clauson, Guthrie, & Buzby, 2008).

School nutrition programs are non-profit operations within school districts, though the details of their partnerships vary by district. They are expected by the school district to break even, without operating indefinitely at a deficit. They receive revenue directly from students and, more significantly, through the federal government’s school meal programs. When the school nutrition program sells reimbursable meals, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) provides payments for meals served that meet the requirements of the National School Lunch Program (NSLP) and/or the School Breakfast Program (U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service [USDA, FNS], 2009). These payments are highest for free meals, followed by reduced-price meals, and finally full-price meals, and are supplemented by any payment made by the purchasing student. Therefore, for the school meal program to be successful, the meals served must meet the requirements and needs of multiple stakeholders: the students, the school district, and the government.

The purpose of this case study was to identify common elements of three diverse school districts that were models, challenges notwithstanding, of the real-world feasibility of improving school meals. An interdisciplinary group of investigators carried out this case study with expertise and a focus on nutrition, economics, agriculture, and sustainability. In addition, the work was in-depth and hands-on. The team ate the school meals and talked with the students, school staff, community members, and school administrators. A primary goal was to stimulate other school districts to apply the lessons learned from this study to make progressive changes in foods served in schools.

Methodology

School District Selection

Public school districts without charter school status from Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Maine were initially identified for potential participation in this study based on two important criteria: 1) school-wide eligibility for free or reduced- price lunches of >40%, to capture programs that serve a large proportion of underserved children; and 2) school district population of >1,000 students with three or more schools, to represent programs that must produce a high volume of meals each day. Data on the percentage of students eligible for free or reduced price lunch in 2008-2009 was accessed through the Anne E. Casey Foundation Kids Count Data Center (The Annie E. Casey Foundation, 2009).

Sixty-eight school districts initially qualified based on these criteria: 34 of 392 districts in Massachusetts, 9 of 191 districts in New Hampshire, and 25 of 179 districts in Maine. In January 2010, letters were sent to the superintendents and school nutrition directors in each of the qualified districts to provide advance notification that the school nutrition director would be contacted in the upcoming weeks for a brief phone screening. The purpose of the screening was to determine the extent of positive school nutrition changes that had taken place since 2005, and to gauge the level of interest in participating in the study. School districts were informed that they would receive $5,000 for their participation.

During screening calls (February 2010), a brief questionnaire was administered to determine whether the school district: 1) independently operated their own school nutrition system; 2) was fiscally solvent; and 3) had implemented significant positive change(s) to school food in the past five years. Criteria for positive change included: increasing availability of fresh fruits, vegetables, and whole grains in school meals; reducing the availability of processed foods (less added sugar, sodium, saturated fat, and trans fat); and being involved in a farm-to-school program. Questions were also asked about changes in leadership, equipment, policies and training.

For the 12 schools that met all the specified criteria, a second phone interview was conducted to gather specific information on the positive changes in these districts. Three school districts were selected to balance the following elements: 1) significant progress in improving school nutrition; 2) inclusion of one school district from each state; 3) representation of communities of various sizes and diverse populations.

Selected School Districts

The three districts chosen for in-depth assessment were Chicopee Public Schools in Chicopee, Massachusetts, Laconia School District in Laconia, New Hampshire, and Maine School Administrative District 3 (MSAD3) in Unity, Maine (Table 1).

Table 1. Demographics and Characteristics of the Three School Districts Examined.

| Demographic Category | Chicopee, MAa |

Laconia, NHb |

MSAD3, MEc |

| Population | 54,428 | 16,411 | 11,000 |

| Students enrolled | 7,875 | 2,220 | 1,440 |

| Elementary School | 9 | 3 | 6 |

| Middle School | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| High School | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Otherd | 2 | ||

| Graduation Rate | 70.6% | 81.0% | 80.5% |

| Race | |||

| Caucasian | 65% | 94% | 97% |

| Hispanic | 27.5% | 1.4% | 0% |

| Black/African American | 3% | 1.1% | 1.5% |

| Othere | 4.5% | 3.5% | 1.5% |

| Language other than English spoken at home | 20.8% | 8.3% | 0.13% |

| Median Household income | $44,284 | $37,796 | $16,394 |

Chicopee is the second largest city in western Massachusetts and was chosen as an urban district for the study. The Laconia School District is located in the Lakes Region of New Hampshire was selected to represent a mid-sized district. MSAD3, which covers 490 square miles and an estimated population of about 11,000, is based in Unity, Maine and was chosen to represent a rural school system.

Data collection in the selected districts

Two additional in-depth phone interviews with the school nutrition director from each district were completed to obtain a detailed understanding of finances, environment, and timeline of changes made. The research team conducted a site visit to each district in spring (April/May) 2010. The visits included: tours of the school nutrition operations and facilities within the elementary, middle, and high schools; taste tests by the study team; and interviews with key informants, including students, school nutrition staff, school district leadership, wellness instructors, teachers, and community partners. Each visit was guided by the school nutrition director and endeavored to increase the study team’s understanding of what prompted positive changes, how they were or are being implemented, and what challenges were faced. Additional emphasis was placed on identifying individuals and relationships that were critical for initiating and sustaining improvements. Following site visits, the school nutrition director and/or key informants were contacted directly by the research team with additional questions to fill in data gaps. This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at Tufts University.

Results And Discussion

In each of the school districts, over half of the lunches served were free or reduced-price (Table 2). In 2010, about half of all public school students were eligible for free or reduced-price lunch and 65% of the lunches served were free or reduced-price (USDA, FNS, 2011); the case study communities were representative of this national data. With students from lower income households eating the majority of lunches served, reimbursable meals provide an important source of nutrition for students who may not always have access to healthful food choices and meals away from school.

Table 2. Annual School Lunch Participation and Reimbursement Characteristics for School Year 2009-2010a

| Demographics | Chicopee, MA |

Laconia, NH | MSAD3, ME |

| Percentage of students eligible for free or reduced-price lunch (FRP) | 60% | 55.5% | 70.8% |

| Of students eligible for FRP, percentage participation | 78% | 74.5% | 70% |

| Total number of lunches served | 867,399 | 277,045 | 176,520 |

| Total free & reduced-price lunches served (percentage) | 676,571 (78%) | 186,174 (67%) | 135,920 (77%) |

| Annual amount of federal reimbursement for free & reduced-price lunches | $2,696,724 | $683,702 | $370,433 |

With the unique expertise areas of the research team, information in the areas of nutrition, economics, agriculture and sustainability was collected and analyzed. Based on the qualitative data collected, eleven specific “ingredients” for dynamic improvements in the quality of school food were identified (Figure 1). The steps to change were varied, evolutionary, and continuous over a period ranging from 3-20 years. The list of ingredients begins with the top priority, “Kids First” and continues with ingredients that fit into three categories: “Gradual Change,” “Smart Economics,” and “Building Strong Relationships.”

Putting Kids First

In each of the case study districts, the guiding principle of “Kids First” was emphatically echoed by the school nutrition director and district leadership. Selecting the health and well-being of the students as the top priority is central to driving change. As modeled in the school districts studied, when the school nutrition director, administrators, and community focus on “what is best for the kids,” the path to improvement becomes clearer and barriers are reduced

Gradual Change

Slow introduction of new foods. School staff agreed that experimenting (“taste test” days) and several introductions of new foods over time were necessary for student acceptance of new foods. In some cases, the introduction of new foods was planned to coincide with classroom activities, such as cultural celebrations, that may have improved the food’s acceptability. These activities were considered integral to encouraging students eat and enjoy healthier foods. Research demonstrates that with repeated exposure, students’ preferences for different foods increases (Wardle, Herrera, Cooke, & Gibson, 2003).

Smart Economics

High participation rates for reimbursable meals. Increasing participation in the school nutrition program is the most effective way for a school nutrition program to stabilize revenue while pursuing the goal of increasing healthful meals. In each of the districts studied, increased revenue from high participation rates allowed leadership to pursue beneficial changes. The school nutrition programs developed and maintained high participation rates by building student loyalty and consistently delivering high-quality reimbursable meal options. In one district, the administration made it easier and less stigmatizing for eligible students to sign up and pay for free or reduced-price meals by using technology, such as electronic benefit transfer (EBT) cards. Efforts to increase participation in the federal meal programs is a strategy to buffer financial losses that may initially result when types of school food and preparation techniques are changed (Wharton, Michael, & Schwartz, 2008).

Innovative food storage. The school nutrition departments in this study emphasized their efforts to 1) stretch locally grown foods outside of their seasonal availability by freezing; 2) take advantage of beneficial commodity pricing by purchasing and then and storing items if not used immediately; and 3) utilizing inventories of frozen and stored food as the school year comes to a close. They noted that this requires flexibility and foresight on the part of the staff, and frequent assessment of food inventory.

Routine equipment purchasing and maintenance. Study participants all budgeted for capital investments and maximized opportunities to apply for equipment grants. Conducting routine maintenance on existing equipment was also critical to maintaining efficiency and preventing costly repairs/replacements, even if up-front costs were high.

Maximization of federal USDA foods program dollars. USDA foods, previously known as commodities (grains/breads, meat and meat alternatives, vegetables/fruits, and other foods), are available to schools participating in the NSLP. Widely using federal commodity program dollars helped case study participants reduce meal costs, even when savings were partly offset by the labor needed to prepare these foods. School nutrition program staff noted they economized by purchasing unprocessed USDA foods, focusing on more expensive protein sources and commodities that other districts were under-utilizing, thereby making them less expensive.

Capitalize on grant opportunities. All three districts in this study participated in the federal Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Program, which allows them to offer their students otherwise unaffordable fresh produce (United Fresh Produce Association, 2011). Taking time to secure grants and other funding opportunities was found to be an asset. School nutrition budgets may be augmented with funding from public and private grants, providing funds for equipment, professional development, fresh food, and other valuable improvements. Each of the participating districts received grant money from at least one other source, either public or private, and found the additional funds to be essential in making progressive changes while achieving financial solvency, even if additional labor was needed to prepare the grants.

Reduce Waste. In the Maine school district, the school nutrition department eliminated trays, adopted portion-controlled plates, and transitioned to permanent silverware. These progressive changes, in tandem with a high school student group dedicated to promoting recycling and composting, resulted in a dramatic 77% reduction in waste in just one year. In the high school, student volunteers monitored the trash during the lunch period so that waste was properly composted and recycled. Collaboration between the school nutrition program and the student body was essential in achieving this reduction in waste. Reduction in waste was cost effective, while benefitting the environment, and may be achieved through a variety of strategies, including recycling food packaging, participating in a composting operation, or providing students with sufficient time to complete their meals.

Buy Cooperatively. Both the Maine and Laconia school districts reported that cooperative buying with neighboring districts resulted in substantial short- and long-term payoffs, especially because of their smaller district size. Partnering with neighboring school districts to purchase cooperatively was cost effective by improving results of price negotiations.

Build Strong Relationships

In addition to stewarding change, school nutrition directors in this study consistently created and maintained strong relationships within the school nutrition department, the district, and the community. In each of the school districts studied, the school nutrition director met regularly with district leadership and community partners to discuss challenges and opportunities. Developing strong private and public partnerships has been advocated by USDA to help to increase the cost effectiveness of school nutrition operations (USDA, FNS 2007).

Promote leadership. Study participants reported that building relationships within and outside of the school nutrition department, including obtaining support from school administrators, was critical to making progress. The participating school nutrition directors established relationships with the local school board, and indicated that considerable savings could be achieved if the local school board agrees to cover overhead costs, such as electricity, garbage, recycling, and/or employee health care. The benefit of this has been noted elsewhere (Wagner, Senauer, & Runge, 2007). Also, positive relationships with the community were built through collaboration on school wellness policies (USDA, FNS, 2007). In addition, supporting professional development for members of the school nutrition team improved both the quality of the work and the relationships within the organization. In Chicopee, the school nutrition director suggested that staff development is the single most important component of achieving change. The USDA also considers investing in professional development for staff to be a “guiding principle” in improving school meals.

Engage stakeholders and community. Partnering with local farms and vendors, for example, fosters positive relationships and allows for easier local purchasing. In Laconia and Maine, the districts worked with individual farms to source foods such as apples and to assist with educational activities. In the Maine district, the school nutrition director worked with more than a dozen farms to purchase fruit, vegetables, bread, and meat. Remarkably, this northern rural school district spends more than 40% of its total budget on food from local sources. In Chicopee, the school nutrition director partnered with a single, large vegetable farm that aggregated produce from other nearby farms for distribution to the schools. When the delivery of fresh, local produce peaked during the summer months, the school district served nearly 3,000 meals per day through its summer meals program. During this time the school nutrition staff also processed and froze local berries for use in the fall. These approaches also help to cement a relationship between the school district and the community that it serves and has a multiplier effect for the local economy.

Summary: Five Common Strategies

Researchers found that the three school districts in this study each had a universal commitment to give school children access to healthful foods. Achieving continued improvements required both structural changes to the school food environment and efforts to change individual behaviors of staff and students. In the case study districts, these two approaches combined over time to build a culture supportive of healthful eating. Positive benefits of fostering an organizational culture change may include achieving related financial savings in school settings (Schelly, Cross, Franzen, Hall, & Reeve, 2010).

After examination of key strategies leading to positive change, five common strategies provided a framework for success: 1) cooking more; 2) serving fresh fruits and vegetables; 3) making changes in competitive foods; 4) creatively sourcing healthful foods; and 5) connecting food with the environment and good health. Healthful foods were obtained from a variety of sources, including local and regional vendors, farms, and the USDA foods program, with a common thread of flexibility to maximize opportunities for positive change.

Conclusions And Application

Considering the health and well-being of the students above all other priorities was essential in each of the case study districts. Creativity, innovation, business acumen, and strong leadership were identified as central to making improvements in school food environments. The school nutrition directors in the study communities provided leadership for positive change in the quality and healthfulness of food served. More details on their “stories” are included in a public report released by the Harvard Pilgrim Healthcare Foundation (Sacheck, Economos, Griffin, & Wilde, 2010) that is available at: https://www.harvardpilgrim.org/portal/page?_pageid=213,379824&_dad=portal&_schema=PORTAL.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Harvard Pilgrim Healthcare Foundation for their financial support of the project along with gratefully acknowledging the help of the three school nutrition programs and directors of Chicopee, Massachusetts, Laconia, New Hampshire, and Unity, Maine school districts: Joanne Lennon, Tim Goosens, and Cherie Merrill. We would also like to thank Nancy Fisher for her management assistance and thoughtful contributions throughout the project and Angel Park for her assistance with data collection. Without their support this research would not have been possible.

References

Murray, N., Low, B., Hollis, C., Cross, A., & Davis, S. (2007). Coordinated school health programs and academic achievement: a systematic review of the literature. Journal of School Health, 77, 589-600. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2007.00238.x

Ralston, K., Newman, C., Clauson, A., Guthrie, J., & Buzby, J. (2008). The National School Lunch Program Background, Trends, and Issues (USDA, Economic Research Report No. 61). Retrieved from http://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/err61/err61.pdf

Sacheck, J., Economos, C., Griffin, T., & Wilde, P. (2010). Dishing Out Healthy School Meals: How Efforts to Balance Meals and Budgets are Bearing Fruit (Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Foundation Report). Retrieved from https://www.harvardpilgrim.org/pls/portal/docs/PAGE/MEMBERS/STAGING/FOUNDATION_OLD/HEALTHYMEALS.PDF

Schelly, C., Cross, J., Franzen, W., Hall, S., & Reeve, S. (2010). Reducing energy consumption and creating a conservation culture in organizations: A case study of one public school district. Environment and Behavior, 43, 316-343. doi: 0.1177/0013916510371754

The Annie E. Casey Foundation. (2009). Kids count data center. Retrieved from http://datacenter.kidscount.org/

United Fresh Produce Association. (2011). The fresh fruit and vegetable snack program. Retrieved from http://www.unitedfresh.org/ffvp

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service. (2007). The road to success: A guide for school foodservice director. Retrieved from http://www.fns.usda.gov/tn/Resources/roadtosuccess.html

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service. (2009). National School Lunch, Special Milk, and School Breakfast Programs, National average payments/maximum reimbursement rates. Federal Register, 74, 34304-34306. Retrieved from http://www.fns.usda.gov/cnd/governance/notices/naps/NAPs09-10.pdf

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service. (2011). Child nutrition tables. Retrieved from http://www.fns.usda.gov/pd/cnpmain.htm

Wagner, B., Senauer, B., & Runge, C. (2007). An empirical analysis of and policy recommendations to improve the nutritional quality of school meals. Review of Agricultural Economics, 29, 672-688. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9353.2007.00380.x

Wardle, J., Herrera, M., Cooke, L., & Gibson, E. (2003). Modifying children’s food preferences: The effects of exposure and reward on acceptance of an unfamiliar vegetable. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 57(2), 341-348. doi:10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601541

Wharton, C. M., Michael, L., & Schwartz, M. B. (2008). Changing nutrition standards in schools: The emerging impact on school revenue. Journal of School Health, 78(5), 245-251. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2008.00296.x

Biography

Sacheck, PhD is Assistant Professor, Friedman School of Nutrition, Tufts University. Morgan is Doctoral Candidate, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. Wilde, Griffin, and Economos are Associate Professors, Friedman School of Nutrition, Tufts University. Nahar is Program Manager, Children’s Hospital, Boston.

Purpose / Objectives

This case study identified common elements of three diverse New England school districts that were real-world models of improving school meals.