Volume 40, Issue 2, Fall 2016, Fall 2016

Increasing Fruit and Vegetable Consumption During Elementary School Snack Periods Using Incentives, Prompting and Role Modeling

By Stephanie M. Lopez-Neyman, MS, MPH, RD, LD; Cynthia A. Warren, PhD

Abstract

American children’s consumption of fruits and vegetables (FVs) does not meet current recommendations. Hence, several federally funded, school-based programs have been initiated over the last several years. One such program is the United States Department of Agriculture Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Program (FFVP), which provides FVs free of charge to elementary school children 2-4 days per week. The objective of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of several behavioral and environmental interventions to increase the proportion of students bringing and consuming FV snacks from home on days when they are not provided through the FFVP.

Full Article

Regular consumption of fruits and vegetables (FVs) is associated with better weight management, improved short-term health outcomes and reduced risk of a variety of costly chronic diseases (He, Nowson & MacGregor, 2006; Hu, 2003; Hung et al., 2004). These benefits led the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) to recommend FV consumption as an important component of a healthful diet (2010). However, FV intake among American children is typically well below USDA recommended guidelines (Eaton, et al., 2012; National Cancer Institute, 2013). Furthermore, not only do rates of childhood obesity correlate positively with later life weight measures, but children’s food preferences tend to persist into adolescence and adulthood as well (Singh, Mulder, Twisk, Van Mechelen & Chinapaw, 2008). Therefore, programs aimed at increasing children’s consumption of FVs can help improve not only their health outcomes, but can have longer lasting personal- and societal-level implications.

One such program, the USDA Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Program (FFVP), was piloted in 2002 through the Farm Security and Rural Investment Act and was subsequently expanded nationwide in 2008 through the Food, Conservation, and Energy Act (USDA-Food & Nutrition Service [FNS], 2013b). The purpose of the FFVP is to increase the variety and amount of FVs children experience and consume, with the long-term goals of positively influencing lifelong eating habits and combating obesity. The FFVP provides funding for schools to serve free FV snacks to students outside of reimbursable food programs (e.g., school breakfast or lunch). The program is specifically designed for elementary schools where at least 50% of students qualify for free or reduced priced school meals (family’s income is 185% of the U.S. federal poverty level or below); thus, the program serves children who may be in the most need of nutritional assistance. Each participating school receives $50-$75 per student annually to cover costs of serving FV snacks.

Several studies have examined the impact of the FFVP, finding a variety of positive outcomes related to children’s attitudes and preferences toward FVs, as well as increases in overall FV consumption (Bica & Jamelske, 2012; Coyle et al., 2009; Davis, Cullen, Watson, Konarik & Radcliffe, 2009; Jamelske & Bica, 2012; Jamelske, Bica, McCarty & Meinen, 2008; Ohri- Vachaspati, Turner & Chaloupka, 2012; USDA-FNS, 2013). Despite these positive effects, research has also shown the impact of the FFVP may not extend beyond the snack period in which students are served free FVs (Coyle et al., 2009; Jamelske et al., 2008; USDA-FNS, 2013a). For example, even after experiencing many months of the FFVP, students attending schools that permit them to bring food from home to eat as a snack do not bring FVs to eat on days when free snacks are unavailable through the FFVP (i.e., non-FFVP days), and their FV consumption outside of school does not necessarily increase (Bica & Jamelske, 2012; Jamelske & Bica, 2012). A number of factors can affect the limited behavior change associated with the FFVP, including the presence or absence of healthful eating options, and a lack of positive role models (combined with the presence of negative role models) (Lowe & Horne, 2009). Therefore, a more complete analysis of the factors that extend FV consumption beyond the free snacks served through the FFVP is warranted.

Several initiatives have attempted to make the consumption of FVs more immediately valuable to children by programming additional external positive reinforcers, such as verbal praise, social recognition and prizes (e.g., Cooke et al., 2011). If effective reinforcers can be identified, their use can entice students to increase their experience with FVs, whose natural rewards—delivering good flavor, higher energy levels and improved diet quality—could lead them to continue eating FVs regularly even after external rewards end. For one such study focusing on the school lunch period, Just and Price (2013) randomly assigned schools to one of five different reinforcement conditions that varied in terms of incentive type, size and timing. Findings indicated that incentives were capable of increasing the proportion of children eating a serving of FVs during lunch by 80%. Findings also indicated that rewards produced a greater effect at schools with higher proportions of students receiving free and reduced price lunch, suggesting this type of rewards program can successfully target children who may otherwise have less access to higher priced items like fresh produce.

In another study, Hendy, Williams and Camise (2005) found reinforcement to be effective in increasing children’s FV consumption in their evaluation of the Kids Choice program. Observers recorded consumption of FVs served as part of school lunches to 1st, 2nd and 4th grade students, and provided token reinforcers by punching holes into nametags worn by the students each day they ate these foods. Students would then be able to trade the tokens for prizes. Results indicated this procedure was effective in increasing fruit and vegetable consumption, and that the increases lasted for the duration of the program. Two weeks after completion of the Kids Choice program, participants had increased their FV preference ratings above baseline levels. However, at seven months post-program, FV preferences returned to baseline levels, suggesting the variables necessary for keeping children’s food preferences at heightened levels over time warrant further investigation.

Another initiative that successfully employed positive reinforcement (prizes, classroom wall charts) and role modeling to alter children’s behavior over time and to create norms around the importance of eating FVs is called the Food Dudes Program (Lowe & Horne, 2009). Students are first exposed to super heroes known as the “Food Dudes” through written material and videos.

The Food Dudes act as influential role models for FV consumption. When children participating in the program consume FVs they are awarded small prizes. Classroom wall charts are also used to record consumption levels, which earn further rewards and Food Dudes certificates (Lowe & Horne, 2009). Extensive evaluation of this program showed significant, long-term increases in consumption by children from 2 to 11 years of age across a wide range of FV varieties (Lowe & Horne, 2009). However, despite evidence of efficacy, these programs can be costly, time consuming and labor intensive to put into practice, which may deter school staff and parents alike (Baranowski et al., 2000; Bauer, Yang & Austin, 2004; Burchett, 2003). For schools that already have the FFVP in place, such multi-component programs may not be necessary.

Extending the reach of the FFVP can come from interventions simple in design, resulting in easy implementation and high acceptability.

The objective of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of several behavioral and environmental prompts to increase the proportion of students bringing and consuming FV snacks from home on non-FFVP days. Elementary school students enrolled in a FFVP-funded school and their classroom teachers were participants in this study. This study made use of a “within subjects” experimental design, where students in each classroom were exposed to all of the programmed conditions.

Methodology

The University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire’s Institutional Review Board approved all materials and procedures used in the study. Given the research design, the study qualified for expedited review.

Participants

Researchers recruited students from the two 4th grade and two 5th grade classrooms at a Wisconsin FFVP school to participate in this study. This site was selected because it was the only school in the researchers’ geographic region to be in the first year of FFVP funding, with no prior experiences with data collection on program implementation/outcomes. School administrators gave approval for this research study. Parents provided passive consent for their children’s participation; recruitment letters including a permission form were sent home with all students. Parents were instructed to sign and return the form only if they did not want their child to participate in the study. As is typical when families are asked by schools to participate in activities involving potential costs, the recruitment letter sent to parents notified them that FVs would be available at school to any students whose families would suffer financially if expected to bring them from home. Teachers in the four classrooms also gave their consent to participate in the study, as they served the important roles of implementing the interventions and collecting FV consumption data from students.

Materials

Fruit and Vegetable Consumption Data Sheets. Classroom teachers used data recording sheets to document FVs students brought from home and consumed during snack periods on Wednesdays and Fridays, the two non-FFVP days. The data recording sheets took the form of weekly calendar pages listing student names (alphabetically and vertically), with days of the week appearing horizontally. For the purpose of this study, a FV was operationally defined as “consumed” and, therefore, recorded on the data sheets if the student ate at least half of the snack. Instances when students ate less than half of the FV they brought from home were not recorded. Teachers were trained to conduct observations and record data during a two-hour meeting facilitated by the researchers.

Program Incentives. Several incentives for students were used in the study, including stickers (placed on weekly calendar charts, which were larger in size but similar in design to the data collection calendar pages used by teachers) along with a variety of prizes (e.g., books, glitter pens, puppets, playing cards, super balls, coupons for computer time in the classroom).

Classroom teachers did not receive any incentives for their participation.

Procedure

School cafeteria staff distributed free-of-charge FVs to students and their teachers on Mondays, Tuesdays and Thursdays from October to April, resulting in 95 FFVP days (66 fruits and 29 vegetables served). Students ate the free FVs during an organized afternoon snack period they shared with teachers, separate from any other school activities. Wednesdays and Fridays were non-FFVP days, meaning the school did not provide free FVs to students through the FFVP on these days (49 such days included in the study period).

During the first phase of the study (Condition 1), baseline data were collected indicating numbers of students who were bringing FVs on non-FFVP days prior to any interventions. The baseline phase lasted three weeks and included six non-FFVP days. During this time, students were not exposed to any designed incentives, prompting or teacher modeling aimed at consuming FVs brought from home.

The first intervention (Condition 2) lasted three weeks and included six non-FFVP days. This phase involved students earning stickers contingent upon bringing and eating FVs from home during the afternoon snack period. Students meeting the criterion were allowed to choose a sticker to place next to their name on the weekly calendar chart hanging in a prominent location in their classroom.

Condition 3 lasted two weeks and included four non-FFVP days per classroom. This phase assessed whether a more substantial reward could motivate higher levels of behavior change, providing students with prizes contingent upon bringing and eating FVs on non-FFVP days. During this phase, instead of earning a sticker, students who met the criterion were able to choose one of several available small prizes. There was no limit on the number of prizes students could earn during the study.

After observing higher rates of Teacher B’s students (4th grade, 23 students) bringing FVs for snack periods, an additional condition was included in the study. The researchers learned that Teacher B was employing a prompting strategy (i.e., she included “bring a FV from home” in the list of homework reminders written on the chalkboard for non-FFVP days). Additionally, Teacher B had been bringing and eating her own FV snacks (modeling), talking to her students about the importance of eating FVs as part of a healthful diet and delivering verbal praise to those students who brought and ate a FV snack. The three other teachers confirmed they had not employed any similar strategies. In response, Condition 4 was included in which all four teachers were instructed to implement (or continue) each strategy in combination: prompting (i.e., homework reminder system), verbal praise, prizes and modeling. Data were collected on this final phase for seven weeks, which included 14 non-FFVP days.

Data Analysis

This study utilized a “within subjects” design in which students in each classroom experienced all experimental conditions. Results are displayed graphically as the proportion of students bringing FV snacks across conditions. The sample size limits the utility of inferential statistical analyses in assessing population estimates; results are instead provided descriptively.

Results And Discussion

Sample Characteristics

Seventy-six students participated (45 4th graders, 31 5th graders), representing 100% of class enrollment. Due to routine absences, an average of just over 70 students were present each day across the 49 days studied. School administrators provided age, gender and race/ethnicity data for students. They averaged 9.6 years in age (SD = .70), and 51.6% of the sample was female. The sample consisted of 72 students who identified as White, 3 as African American and 1 as Hispanic/Latino(a). Although confidentiality issues prevented school administrators from reporting the number of students in the sample qualifying for free or reduced price school meals, this value was 58% across the approximately 300 enrolled students. None of the participating students’ parents elected to ask the school to provide their child with free FV items for this study, an option mentioned in the recruitment letter for families facing financial hardship.

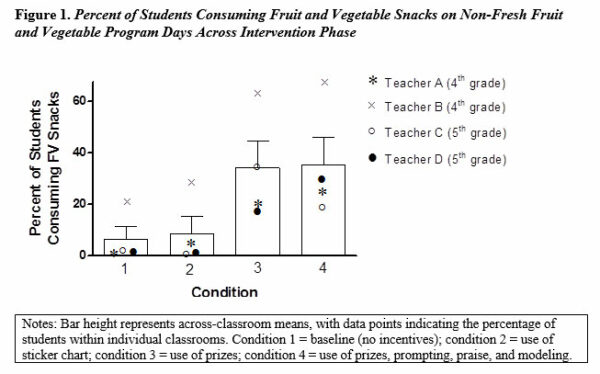

Fruit and Vegetable Consumption on Non-FFVP School Days Across Interventions Results are presented as the percent of students bringing and consuming a FV on non-FFVP days. Figure 1 displays these results as averages for each of the four conditions (open bars); within each condition, data points indicate specific percentages separately for the four different classrooms.

During the initial baseline (Condition 1), a total of 27 instances were observed out of 394 possibilities (i.e., students were bringing and consuming FVs on fewer than 7% of possible instances). In three of the classrooms, consumption of FVs during snack periods was virtually non-existent, with 0, 1 and 2 total instances observed in those classrooms. Teacher B observed somewhat higher baseline rates of FV consumption in her classroom (24 instances out of 114 observations).

In Condition 2 (use of stickers), negligible increases in consumption were recorded with average percent increasing from 6.9 in baseline to 10.1 (42 instances recorded out of 414 student observations). Condition 3 involved additional prizes (e.g., books, glitter pens, puppets, playing cards, super balls, coupons for computer time), which were associated with an increase of bringing and consuming FVs to nearly 40% (98 instances out of 269 observations). Examinations of the individual data indicate this increase was consistently observed across the classrooms, with increases noted relative to each teacher’s starting baseline levels. Teacher B maintained the highest numbers of students bringing and consuming FV snacks, with 56 positive instances out of a total of 88 observations. On average, nearly 15 of Teacher B’s 23 students brought a FV from home to eat each of the days in this phase.

As noted earlier, Teacher B revealed to the researchers that she had been implementing additional strategies not accounted for in the initial study design (i.e., verbal praise, prompting and modeling). Therefore, researchers ran a subsequent condition in which each strategy was utilized (prompting, verbal praise, modeling and prizes) for the remainder of the academic year. Condition 4 in Figure 1 displays the results from the final period. On average, results were very similar to those obtained in the 3rd condition, with students bringing and eating FVs for snack periods 37.1% of the time (compared to 36.4% during Condition 3).

Fruits and Vegetables Brought From Home for Non-FFVP Days

Table 1 shows the variety of FVs students brought from home and consumed on non-FFVP days.

| Table 1. Total Numbers of Fruits and Vegetables Students Brought From Home to Consume During Snack Periods on Non-Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Program (FFVP) Days | |||||

| Fruits | Vegetables | ||||

| Apple | 298 | Applesauce | 7 | Carrot | 94 |

| Orange | 130 | Cantaloupe | 6 | Cucumber | 13 |

| Banana | 107 | Peach | 6 | Celery | 8 |

| Grapes | 59 | Dried Pineapple | 5 | Broccoli | 6 |

| Tangerine | 52 | Grapefruit | 4 | Spinach | 5 |

| Raisins | 39 | Blueberries | 3 | Cauliflower | 4 |

| Craisins | 36 | Dried Apricot | 3 | Green Pepper | 2 |

| Pear | 21 | Tomatoes | 2 | Jicama | 2 |

| Mixed Fruit | 20 | Pomegranate | 2 | Lettuce | 2 |

| Strawberries | 20 | Apricot | 1 | Pea Pods | 2 |

| Kiwi | 17 | Boysenberries | 1 | Mixed Vegetables | 1 |

| Watermelon | 16 | Raspberries | 1 | Radish | 1 |

| Dried Apple | 13 | Rhubarb | 1 | ||

| Pineapple | 9 | ||||

| Total: 879 | Total: 140 | ||||

| Note: 4th and 5th grade participants (N = 76) from the FFVP-funded elementary school brought these 1,019 fruit and vegetable items to consume during snack periods for the 49 non-FFVP days included in this study. | |||||

Of the 1,019 items listed, 86.3% are fruits and 13.7% are vegetables. Although the majority of these FVs are popular among children of this age, especially items with the highest frequencies (i.e., apple, orange, banana, carrot) (Burchett, 2003; Hendy et al., 2005), the sample nonetheless reflects a good deal of variety.

Conclusions And Application

Applications of Current Study

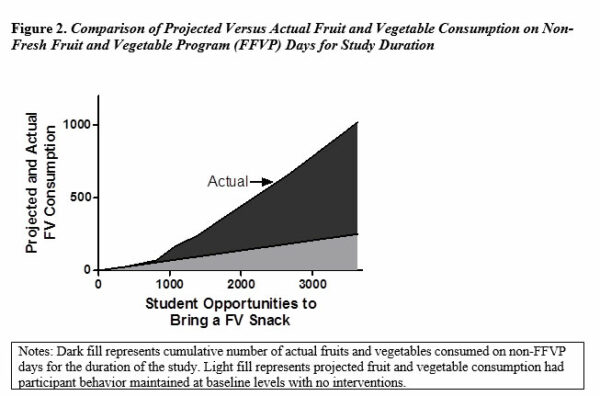

Increasing children’s exposure to FVs can have important short- and long-term health implications. The current study demonstrates how the use of incentives, modeling and praise can increase everyday FV consumption. As projected by their initial baseline levels (see Figure 2), it is possible that had the program interventions not been implemented, participants in this study would have (as a group) consumed a total of only 251 FVs during non-FFVP snack days over the 27-week time period.

Instead, the interventions were associated with consumption of 1,019 FVs, as displayed by the darker fill area in Figure 2 representing the cumulative recorded FV consumption over the academic year (not counting FVs provided by the FFVP). Although the use of what we term “small” incentives (stickers) was not effective in increasing consumption of FVs, the use of “larger” incentives was. These prizes were not necessarily more expensive, but rather represented more varied options available to the participants. Some of these options were not tangible reinforcers at all, but instead were activities that cost nothing to provide (e.g., extra computer time).

There have been several over-arching theories put forth to predict what might function as a reinforcer, including Premack’s Principle (Premack, 1959) and Response-Deprivation Theory (Allison, 1993; Timberlake & Allison, 1974). What these theories can add to this analysis is that certain activities (such as access to computer games or reading time) can function as reinforcers so long as people are deprived of the activity below their preferred baseline levels—how time would be allocated among activities when no constraints are in place. To find activities that are desirable to a large number of students, a teacher could simply have the students report typical activities in which they like to engage; schools would then offer access to those types of activities contingent upon students bringing FV snacks. This could be a method of implementing a variety of reinforcing activities with little to no cost to schools.

The current approach to increase FV consumption can have longer-term implications as well. Children need repeated exposure to a variety of FVs before they become part of their typical diet (Cooke et al., 2011). Food preferences can be thought of as persistent choices for certain foods based on several potential consequences, including immediately inherent reinforcing consequences (e.g., taste), somewhat delayed reinforcing consequences (e.g., increased energy) or social mediation (e.g., compliance with what others tell the child to do, modeling after peers). People rarely eat food to earn access to a preferred activity or other tangible reinforcer. However, when children are not yet consuming recommended levels of different food categories, these external contingencies can be implemented to increase exposure to a variety of food items short- term. It is at that point that other, more naturally occurring contingencies can ideally be established (e.g., taste enjoyment, preference, availability), as those are what will maintain behavior over the long-term. Ultimately, to be considered successful, an intervention must progress from using the kinds of outcomes featured in this study to more naturalistic reinforcers that have a better chance of maintaining long-term gains in FV consumption (Horne, Fergus Lowe, Fleming & Dowey, 1995).

Whether considering short- or long-term gains, it is important to note that participants brought more fruits from home than vegetables, a finding consistent with general reports that children are more likely to eat fruits than vegetables. In fact, several prior interventions that have successfully increased fruit or fruit juice consumption have had no effect on vegetable consumption (Blanchett & Brug, 2005; Cassady, Vogt, Oto-Kent, Mosley & Lincoln, 2006; Gortmaker et al., 1999). Still, the number and diversity of vegetables brought from home in the current study were not trivial (see Table 1), even though no special efforts were made to encourage students to bring vegetables. Given that U.S. Dietary Guidelines (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services & USDA, 2015) recommend children consume more vegetables than fruits on a daily basis, future interventions that specifically target increases in vegetable consumption could yield significant benefits.

Limitations of Current Study and Ideas for Future Research

Although findings from the current study can provide important insights about the association between use of a variety of rewards and FV consumption, the relatively small size and homogenous characteristics of the sample may limit the generalizability of findings.

Investigations of FFVP-related incentive programs could benefit from conducting controlled trials with a larger and randomized sample population. A large sample size would allow for assessment of intervention response by grade or gender of participants, or socioeconomic status of families. Socioeconomic status, specifically the cost of supplying FVs on non-FFVP days, is also of particular importance from an intervention design perspective. Transferring costs to families can be seen as a benefit of this approach because it reduces the level of resources needed by schools, allowing more schools to participate in programming. However, potential economic barriers to having families secure FVs are not insignificant and need to be addressed for the benefits of this type of program to be fully realized.

Other limitations of the current study are related to intervention design and assessment procedures. The researchers designed this intervention to focus only on changes in consumption during school snack periods, and the duration of this intervention was relatively short. There was no mechanism for measuring impact on health or changes in FV consumption outside of the snack period. Future examinations utilizing longer intervention periods combined with 24-hour data collection periods could more accurately measure potential broader effects of the incentives on children’s health behaviors. Meanwhile, if teachers are to be used in program implementation, careful monitoring of their continued compliance with intervention protocols is needed to avoid the unexpected outcome that occurred in the current study when researchers discovered that one of the teachers was implementing interventions on her own initiative, resulting in inconsistent delivery of the program. Regarding assessment procedures, future researchers may want to include data collected directly from participants themselves and/or from their parents. The current study is also limited by the fact that teachers rather than researchers collected the data and, although teachers had been thoroughly trained, there was no confirmation of accuracy of teacher reports (i.e., student FV consumption).

Finally, future research could more thoroughly examine the components of the current intervention that are necessary and sufficient to enhance consumption of FVs. The implementation of the larger and more varied array of incentives in this study was associated with increased FV consumption during snack periods. Subsequent analysis of the inclusion of prompting, modeling, and verbal praise indicated that combining all components increased FV consumption during snack periods above baseline levels, though not notably above the levels observed with large incentives alone. Future interventions could not only more thoroughly examine the effects of these components singularly, but could also focus on the individual level (rather than group) to better understand why some students are affected by these interventions when others are not. When considering program components, one must not neglect the potential impact of the individual(s) directly responsible for implementation. For example, findings from studies investigating teachers’ attitudes toward classroom-based initiatives to encourage primary schoolchildren to eat FVs show high levels of teacher support (Yeo & Edwards, 2006), and researchers have demonstrated that teacher influence has a significant impact on students’ attitudes toward FVs (Prelip, Kinsler, Chan, Erausquin & Slusser, 2012).

Of potential interest in the current study is the higher number of students from Teacher B’s classroom bringing FVs across all conditions. Some people have a history of employing modeling, prompting and verbal praise in their everyday lives to such benefit that they perform these strategies very naturally to encourage others’ behaviors. This tendency may be what accounts for Teacher B’s results. The fact that Teacher B produced higher numbers does not, of course, diminish the intervention effects because all four teachers showed the same trends across intervention phases relative to their own baseline numbers. The point is that examining baseline levels of performance may alone reveal a potential method for identifying teachers who could show the greatest potential in implementing procedures used in this study. Examining program components, including teacher characteristics, would likely result in more inclusive and comprehensive interventions that could profitably be implemented in future programs.

Conclusion

Findings from the current study are compelling because they can provide a framework for school staff to expand the reach of the FFVP beyond the free availability and accessibility of FV snacks on specified days. Despite many constraints facing teachers and schools, this type of intervention can be feasibly implemented with minimal time and resources. Widespread adoption of effective programs is needed, as current concerns over childhood obesity and its attendant health issues are well founded and urgent. Approaches associated with even moderate gains should be of immediate interest, as they could result in significant positive health impacts for society.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by funding from the University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire’s Office of Research and Sponsored Programs (ORSP). The ORSP had no involvement in study design, data collection or analysis, report writing or the decision to submit for publication. The authors thank Daniel Holt, PhD, for his valuable suggestions regarding study design. The authors also thank undergraduate research assistants Judy Dickinson, Lainee Hoffman, Stephanie Mabry, Kevin Reinhold, April Ross and Laurelyn Wieseman, as well as the students, teachers, administrators and foodservice personnel at the participating school.

References

Allison, J. (1993). Response deprivation, reinforcement and economics. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 60(1), 129-140. doi:10.1901/jeab.1993.60-129

Baranowski, T., Davis, M., Resnicow, K., Baranowski, J., Doyle, C., Lin, L. S., . . . Wang, D. T. (2000). Gimme 5 fruit, juice and vegetables for fun and health: Outcome evaluation. Health Education & Behavior, 27(1), 96–111. doi:10.1177/109019810002700109

Bauer, K. W., Yang, Y. W. & Austin, S. B. (2004). “How can we stay healthy when you’re throwing all of this in front of us?” Findings from focus groups and interviews in middle schools on environmental influences on nutrition and physical activity. Health Education & Behavior, 31(1), 34–46. doi:10.1177/1090198103255372

Bica, L. A., & Jamelske, E. M. (2012). USDA Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Program creates positive change in children’s consumption and other behaviors related to eating fruits and vegetables. Journal of Child Nutrition & Management, 36(2). Retrieved from https://schoolnutrition.org/JCNM/

Blanchette, L., & Brug, J. (2005). Determinants of fruit and vegetable consumption among 6–12- year-old children and effective interventions to increase consumption. Journal of Human Nutrition & Dietetics, 18(6), 431-443. doi:10.1111/j.1365-277X.2005.00648.x

Burchett, H. (2003). Increasing fruit and vegetable consumption among British primary schoolchildren: A review. Health Education, 103(2), 99-109. doi:10.1108/09654280310467726

Cassady, D., Vogt, R., Oto-Kent, D., Mosley, R. & Lincoln, R. (2006). The power of policy: A case study of healthy eating among children. American Journal of Public Health, 96(9), 1570– 1571. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2005.072124

Cooke, L. J., Chambers, L. C., Anez, E. V., Croker, H. A., Boniface, D., Yeomans, M. R. & Wardle, J. (2011). Eating for pleasure or profit: The effect of incentives on children’s enjoyment of vegetables. Psychological Science, 22(2), 190-196. doi:10.1177/0956797610394662

Coyle, K. K., Potter, S., Schneider, D., May, G., Robin, L. E., Seymour, J. & Debrot, K. (2009). Distributing free fresh fruit and vegetables at school: Results of a pilot outcome evaluation.

Public Health Reports, 124(5), 660-669.

Davis, E. M., Cullen, K. W., Watson, K. B., Konarik, M. & Radcliffe, J. (2009). A fresh fruit and vegetable program improves high school students’ consumption of fresh produce. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 109(7), 1227-1231. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2009.04.017

Eaton, D. K., Kann, L., Kinchen, S., Shanklin, S., Flink, K. H., Hawkins, J. & Wechsler, H. (2012). Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance – United States, 2011. Morbidity & Mortality Weekly Report, 61(4), 1-162.

Gortmaker, S. L., Cheung, L. W. Y., Peterson, K. E., Chomitz, G., Hammond Cradle, J., Dart, H., . . . & Laird, N. (1999). Impact of a school-based interdisciplinary intervention on diet and physical activity among urban primary school children: Eat well and keep moving. Archives of

Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 153(9), 975-983. doi:10.1001/archpedi.153.9.975

He, F. J., Nowson, C. A. & MacGregor, G. A. (2006). Fruit and vegetable consumption and stroke: Meta-analysis of cohort studies. Lancet, 367(9507), 320-326. doi:10.1016/S0140- 6736(06)68069-0

Hendy, H. M., Williams, K. E. & Camise, T. S. (2005). “Kids Choice” school lunch program increases children’s fruit and vegetable acceptance. Appetite, 45, 250-263. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2005.07.006

Horne, P. J., Fergus Lowe, C., Fleming, P. F. J. & Dowey, A. J. (1995). An effective procedure for changing food preferences in 5-7-year-old children. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 54(2), 441–452. doi:10.1079/PNS19950013

Hu, F. B. (2003). Plant-based foods and prevention of cardiovascular disease: An overview.

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 78(3), 5445-5515.

Hung, H.-C., Joshipura, K. J., Jiang, R., Hu, F. B., Hunter, D., Smith-Warner, S. A., . . . Willett,

- C. (2004). Fruit and vegetable intake and risk of major chronic disease. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 96(21), 1577-1584. doi:10.1093/jnci/djh296

Jamelske, E. M., & Bica, L. A. (2012). Impact of the USDA Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Program on children’s consumption. Journal of Child Nutrition & Management, 36(1). Retrieved from https://schoolnutrition.org/JCNM/

Jamelske, E., Bica, L. A., McCarty, D. J. & Meinen, A. (2008). Preliminary findings from an evaluation of the USDA Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Program in Wisconsin schools. Wisconsin Medical Journal, 107, 225-230.

Just, D. R., & Price, J. (2013). Using incentives to encourage healthy eating in children. Journal of Human Resources, 48(4), 855-872.

Lowe, C. F., & Horne, P. J. (2009). Food Dudes: Increasing children’s fruit and vegetable consumption. Cases in Public Health Communication & Marketing, 3, 161-185.

National Cancer Institute, Applied Research Program (2013). Usual Dietary Intakes. Retrieved from http://riskfactor.cancer.gov/diet/usualintakes/pop/fruit_total.html

Ohri-Vachaspati, P., Turner, L. & Chaloupka, F. J. (2012). Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Program participation in elementary schools in the United States and availability of fruits and vegetables in school lunch meals. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition & Dietetics, 112(6), 921-926. doi:10.1016/j.jand.2012.02.025

Prelip, M., Kinsler, J., Chan, L. T., Erausquin, J. T. & Slusser, W. (2012). Evaluation of a school-based multicomponent nutrition education program to improve young children’s fruit and vegetable consumption. Journal of Nutrition Education & Behavior, 44(4), 310-318.

doi: 0.1016/j.jneb.2011.10.005

Premack, D. (1959). Toward empirical behavioral laws: I. Positive reinforcement. Psychological Review, 66(4), 219-233. doi: 10.1037/h0040891

Singh, A. S., Mulder, C., Twisk, J. W. R., Van Mechelen, W. & Chinapaw, M. J. M. (2008). Tracking of childhood overweight into adulthood: A systematic review of the literature. Obesity Reviews, 9(5), 474–488. doi:10.1111/j.1467-789X.2008.00475.x

Timberlake, W., & Allison, J. (1974). Response deprivation: An empirical approach to instrumental performance. Psychological Review, 81(2), 146-164. doi:10.1037/h0036101

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service (2013a). Evaluation of the Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Program (FFVP): Final evaluation report. Retrieved from http://www.fns.usda.gov/sites/default/files/FFVP.pdf

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service (2013b). Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Program: Program history. Retrieved from http://www.fns.usda.gov/ffvp/program-history

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture. Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2015-2020, 8th Edition (2015). Retrieved from http://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/guidelines/

Yeo, S. T., & Edwards, R. T. (2006). Encouraging fruit consumption in primary school children: A pilot study in North Wales, UK. Journal of Human Nutrition & Dietetics, 19(4), 299-302. doi:10.1111/j.1365-277X.2006.00706.x

Biography

Bica, Jamelske and Lagorio are all employed at the University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire. Bica and Lagorio are Professor and Assistant Professor, respectively, in the Department of Psychology while Jamelske is a Professor in the Department of Economics.

Purpose / Objectives

Methods

This study was a pre-, post-experimental intervention conducted with 4th and 5th grade students (N = 76) at a FFVP elementary school in Wisconsin. The intervention consisted of three distinct conditions in which teachers provided students with several types of incentives contingent upon bringing and consuming FVs for snack periods on non-FFVP days. Researchers assessed the combined effects of incentives, praise, prompting and modeling.

Results

Results indicated the use of small incentives (stickers) had little impact; however, larger and more varied prizes (e.g., toys, coupons for computer time) and also prompting and modeling strategies increased FV consumption from 7% during baseline to nearly 40%. The interventions increased participants’ FV consumption by an estimated 768 items over the course of the study.

Applications to Child Nutrition Professionals

This study details an intervention for increasing children’s consumption of FVs that could be easily replicable and inexpensive for schools to implement. Increased exposure through the FFVP, accompanied by appropriate incentives and encouragement, can give students a chance to experience the inherent taste and nutritional rewards of FVs while also fostering a behavior pattern that could easily become habitual.