Volume 26, Issue 2, Fall 2002, Fall 2002

Developing a Practical Audit Tool for Assessing Employee Food-Handling Practices

By Mary B. Gregoire, PhD, RD; and Catherine Strohbehn, PhD, RD

Abstract

The purpose of this study was to develop and test an audit tool for assessing employee food- handling practices in school foodservice. The tool was developed using three resources: sample forms and standards used by sanitarians; the California Food Code, which is based on the Food and Drug Administration’s 1999 Food Code, and the National Restaurant Association’s Educational Foundation’s ServSafe® Coursebook. The audit tool’s areas of focus were time/temperature abuse, employee hygiene, and cross-contamination.

The tool was tested by conducting audits of employee food-handling practices in 15 middle school kitchens in the San Francisco Bay Area. Prior to conducting the audits, the researcher trained two observers on appropriate food-handling practices and the protocol for conducting the audits. The researcher and two trained observers each audited five school kitchens.

The audits, conducted in the morning during both preparation and service, lasted for approximately two hours. They indicate that this tool was sensitive to the identification of poor food-handling practices in the facilities during the audit periods, and helped determine that school foodservice employees do not always follow safe food-handling practices. These findings suggest that using an audit tool for routine monitoring may be helpful as part of a continuous self-monitoring program for food safety. This audit tool could be adapted and used by school foodservice directors to conduct self-assessments of employee food-handling practices in their operations.

Full Article

Please note that this study was published before the implementation of Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010, which went into effect during the 2012-13 school year, and its provision for Smart Snacks Nutrition Standards for Competitive Food in Schools, implemented during the 2014-15 school year. As such, certain research may not be relevant today.

More than 27 million school meals are served daily to American children (U.S. Department of Agriculture [USDA], 2001). School foodservice professionals are responsible for the safety of the foods served to children (American School Food Service Association [ASFSA], 1999).

School foodservice employees must follow correct food safety procedures to ensure the safety of the foods they serve (Roefs, 2000). The General Accounting Office (GAO) reported only eight and nine incidents of foodborne illness attributed to school lunch meals in 1997 and 1998, respectively (GAO, 2000). While this is an excellent record of food safety, even one foodborne illness outbreak could be devastating to children and to a school district. For example, a jury awarded a $4.75 million judgment against a school district for an E.coli poisoning that occurred in an elementary school (Cary, 2001). Monitoring food-handling practices is necessary to ensure food safety and to protect customers’ health.

The conditions and practices that impact food safety were investigated in one centralized school foodservice production system (Brown, McKinley, Aryan & Hotzler, 1982). The researchers found that while handwashing facilities were accessible, poor handwashing techniques were observed. In addition, foods were handled directly and employees were eating and drinking while working in the food preparation area. Time-temperature abuses also were observed. Entrees were held for long periods at inadequate holding temperatures.

In another study, sanitation practices in four school production kitchens were evaluated (Gilmore, Brown, & Dana, 1998). Researchers found employees exhibited frequent failure to wash hands and use hair restraints. Contaminated gloves were changed in only half of the researchers’ observations. Sanitation of surfaces, small equipment, utensils, and thermometers was inconsistent and sometimes nonexistent.

Raccach, Morrison, and Farrier (1985) investigated public health hazards in a school foodservice operation using a central kitchen. These researchers found that refrigerated and frozen foods were stored and rotated appropriately. They also observed foods to be correctly covered.

However, employees were observed using bare hands during food preparation; in fact, glove use was observed only twice, and hair restraints were not used at all. In addition, inadequate warewashing and sanitizing was apparent, as was the lack of sneeze-guard protectors.

Three Midwestern elementary schools were studied before and after conversion of their food production system from a centralized to a cook/chill system (Kim & Shanklin, 1999). Time and temperature histories were monitored for spaghetti with meat sauce for three days for both production systems. They found that food items were reheated and held in a steamtable or hot cart for several hours before service due to time and equipment constraints. This inadequate holding was observed to occur both before and after conversion to the new cook/chill system.

Safe food-handling practices need the attention of school foodservice directors. In this study, we developed a practical audit tool to assess employee food-handling practices in school foodservice, and tested the audit tool in 15 schools in the San Francisco Bay Area. This audit tool was developed to assist school foodservice directors in assessing food-handling practices in their districts. Results of such an audit may be used to determine training needs of employees and needs for standard operating procedures. The audit tool also could be used in the training process.

Methodology

Development of the Food Safety Audit Form

An audit tool (Figure 1) was developed based on the following resources: the Santa Clara County, Department of Environmental Health Food Program Official Inspection Report; the California Uniform Retail Food Facilities Law (California’s food code that is based on the 1999 Food Code) (CURFFL, 2000); the National Restaurant Association Educational

Foundation’s ServSafe® Coursebook (1999); and other literature (Bryan, 1982; Neumann, 1998; Reed, 1993).

Figure 1 Foo,J-handling practices audit tool

Lnstructions: SllVfl:!al al iaare i’lc:ludedtoassessIOCd-handlin9 i:-actietS.C “Ye,- whenallemployeespeflcwmall IOOd-hnllir,;tpracticescorredly 100,r. orlhelimetll(r’IQlhediLC:rld:”Mo” •twl bOCMlandl.i’lg pra:tceswerepe11orrood irxooSir.e«lyor ilXtW’fecfly tll(r’IQlhe dil byoneormere &’Yl O)teS. CMck -Nol applied” 10 indie:atlehal IM pra::tke•.lS001relMnl or f’lotObServed dur.no lheaudt

| filod HandlingPractices | YH | No | NA/NO’ | Comments |

| Time/Tempera.hire control | ||||

| 1.Probe-type lh8ffl’letl’lftl!ISareproviOOd lortn0f’lil0ti1’9fffll)eraluies. | ||||

| 2. Emplo-,ees takelffl¥)el’alures01rehealedIOOdS. | ||||

| 3.Emplo-,ees takeif’llllf’l’llllffll)f:ralures01hotandCOidIOOditems. | ||||

| 4.FOOd 1en-.:e-a1u181wetectserved OOin9 taken on theservingline. | ||||

| 5. FOOd 1e•a1u1e:twetectsetVed being taken duringservice. | ||||

| 6.FOOd 1en-.:e-a1u181wetectserved OOin9 taken durir,;iprec:,ara’.iOtL | ||||

| 7. Emplo-,ees rld(IQ8rafp8ctettially trmrtbJSbOd$(PHFs) between l)iejXlra’.ionSlep.$. | ||||

| 8.Emplo-,eesma.i’llainIOOtd«nperairelogs. | ||||

| 9. Thefr’Mf’Mle1’a1reavailablere.-rekiQl!lalOt/lreezer unilS.

fil od/Prepartli.ontservice |

||||

| 1.Mi:w iateulensilsa:e uS&:Itomil’imizeb111el’M:Ieoo1ac1withIOOd. | ||||

| 2. GIO\tsedlcWlged allerSOil.i’lg. | ||||

| 3.Sf(laiate euningboardsareused 10.-PHFsa-id ready-to-eaItOOds. | ||||

| 4.Snoou!)JafdtareusedinIOOdSl!f’licearm.

SIOrl!Jt |

||||

| 1. tnea!S.IXIUl’Y, 300saalOOadreSIIXedbell)# ready-to-eallOOdSinretrigefa’.iontJ’li!S. | ||||

| 2. FOOd iseo- r&:Iti pro1ec1ItemO\ head conraminarioo. | ||||

| 3.FOOd a-id 00-.’fl:!agesarestixeda1leaSI 6″ onIN noor. | ||||

| 4,FOOd isprope(tf laOOleda-Id daled. | ||||

| 5. S1oragelaeillifl:at rekf:tll dean and in O)Odcwd:lr. | ||||

| 6. ToxicialsateSIIXed in aneasejXlra’.errombOd.t.t.oosils.bOdequi)mett, or loedCc.n::I Sufi .

Employee:s |

||||

| 1.Emp10-,ees washlh!i1hanm a11er COt&Vninaling1hem. | ||||

| 2. Hal»-•ilShmesare(l)e:labl!. ao::essihle, a-id supp!i&:I withsoop and11).veJS ind s. | ||||

| 3.Emplo-,ees wear dean dotheS. | ||||

| 4.Emplo-,eesuse hair1estiaints. | ||||

| 5. Emplo-,ees00f’lotuse tlbOO::iOl bOdl)iepara’jQI\IS1ora9e.1<1ishnShingareas. | ||||

| 6.Emplo-,ees00f’lotta1o.-drirlt inloo:!p•alic.-vst llisl’M:ashingareas.

Ulensils/Eq11ipmenVFttiliUe:s |

||||

| 1.FOOd oontaci sul’laeesaoottoosilsatecleaneda-id sanilizedanermuse. | ||||

| 2. Emplo-,eesuse leslsr,ips10 coo:tsatlilizer eooc«trakln. | ||||

| 3.Emplo-,eesuse proper h.Wld dishwashil9 lecflni | ||||

| 4,E ipmMI isCl . oi:e-able, atld in 900d repair. | ||||

| 5. All ulenSilSald containersatekept Cleatl. | ||||

| 6.FIOO(S.wans.aooceilingsarekept deanaooil gOOrdepair.

‘/i’(JIYI””‘appliaabltt“‘ ObSMdd al”‘um,/JIaudil |

The food safety areas or practices chosen for evaluation on the audit form related to the following issues:

- temperature monitoring;

- food storage;

- hot and cold food preparation and service;

- cleaning and sanitation; and

- personal

Time and temperature, cross-contamination, and employee hygiene and handwashing are considered the most frequently observed areas of abuse (Bryan, 1982; Neumann, 1998; Reed, 1993).

The checklist format used for the audit tool enabled three response choices:

- “Yes” indicated that the observed procedure was performed correctly 100% of the time by all employees during the audit;

- “No” indicated that the observed procedure was performed incorrectly or inconsistently during the audit; and

- “Not Applied” indicated that either the procedure was not relevant or it was not observed during the audit.

The audit tool for observing employee food-handling practices was evaluated for content validity by six school foodservice directors whose districts were not included in the audits.

Two observers were trained by the researchers to conduct audits. The observers who were selected had educational backgrounds in nutrition or foodservice management. The training consisted of a two-hour workshop to explain the processes for conducting audits. The researchers explained each item on the audit tool and the appropriate techniques or standard for food handling based upon CURFFL requirements. The workshop included instructions on correct completion of the audit tool. The response terms were defined, and hypothetical situations describing food-handling practices were used to teach observers how to make determinations of adherence to standards. Observers were asked to make determinations for scoring “Yes,” “No,” or “Not Applied.”

After training, pilot-testing in two randomly selected school foodservice operations was conducted to verify inter-rater reliability. Operations used for pilot-testing were excluded from the sample, from which the final 15 test kitchens were chosen. Observations amongst the researcher and two observers were consistent for 90% of the responses. Discrepancies were discussed and total consensus was reached on the process for completing audits.

Recruitment

In November 2000, 7 school foodservice directors were randomly selected from a total of 21 potential study participants. An invitation letter explained the purpose of the study and asked directors to allow audits of the food-handling practices in schools in their districts. One week after the initial mailing either a thank-you or another invitation letter was mailed to respondents and non-respondents, respectively. Five school foodservice directors agreed to participate in the audits and supplied the researchers with a list of onsite kitchens in their districts. Three onsite kitchens from each school district were randomly selected as sites for conducting the audits, comprising a convenience sample of 15 school kitchens.

Conducting the Audits

Audits of employee food-handling practices were conducted during the lunch meal period. They involved approximately two hours of observation during both preparation and service of meals. Most took place between the hours of 10 a.m. and 1 p.m. Days for conducting the audits were chosen at random. The researcher and two trained observers each audited five school kitchens one time during January. The audits were conducted at least one week after the return to school following the holiday break. With agreement by the participating school foodservice directors, all three observers told the onsite kitchen managers that they were foodservice students interested in learning more about school foodservice. This was an attempt to decrease the likelihood of employees changing their food-handling practices due to the observers’ presence.

In addition to completing the audits, researchers gathered demographic data from the school foodservice managers. Managers were asked how long they had spent in their current position, what was their experience in school foodservice, and what was the average number of daily lunches served in their program. After asking the demographic questions, observers kept a low profile during the audits to allow typical production and service procedures to occur.

The food-handling practices in the school kitchens were observed and noted on the audit tool. To ensure confidentiality, all forms were coded with a two-digit site code. Participating school foodservice directors were assured of complete confidentiality.

Statistical Analysis

Audit data were analyzed using frequencies of responses to describe the food-handling practices of the school foodservice employees. Means were calculated to describe demographic characteristics of the sample.

Results And Discussion

Demographics of the Sample

Audits of employee food-handling practices were conducted at 15 onsite middle school kitchens in order to test the use of the audit tool. The mean length of time that managers were employed in their current position was 9 years, and in school foodservice overall it was 16 years. The mean number of lunch meals served daily was 430, with a range from 80 to 1,800. All managers used a conventional system, and none served the same menu item during an audit. In each of the operations, the managers had received formal food safety training and their certificates were displayed.

Results of the Audit Process

The audit tool was considered easy to complete and resulted in the identification of some areas of noncompliance with safe food-handling procedures in the schools participating in this study.

Further, the audit tool appears to provide consistency of results among multiple observers, since

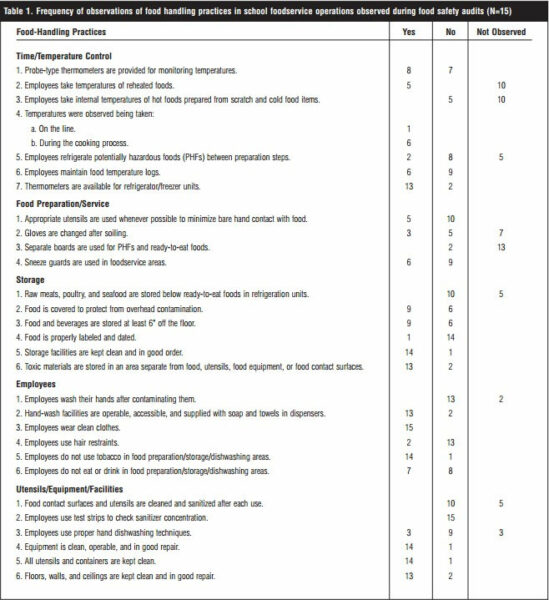

it indicated patterns of food safety abuses among school foodservice kitchens during the food safety audits. The audit results are presented in Table 1.

The poor food-handling practice most frequently observed was related to time and temperature. In 10 kitchens, employees were not observed taking internal temperatures of hot food at any time during pre-preparation. Cold food temperatures were never taken during the observations in all 15 audits. The second most frequent abuse observed was the lack of thermometers available for taking food temperatures. A probe-type thermometer is required by CURFFL for taking food temperatures and was present in only 8 of the 15 kitchens. Just 6 of the 15 kitchens kept temperature logs of food items. The third most frequently observed food-handling problem was failure to transfer foods to cold storage during preparation steps. Cold and frozen foods were observed outside of cold storage for the duration of the audit in 8 of the 15 kitchens. Food thawing at room temperature also was observed.

During preparation and service, the most frequently observed problem was the handling of food with bare hands. When gloves were used, they were not changed between tasks in 5 of the 15 schools observed. The second most common problem was the lack of sneeze guards on the serving lines. Nine of the 15 kitchens did not have sneeze guards.

Several poor food-handling practices were identified related to storage. In 9 of the 15 kitchens, refrigerated food items were covered to protect them from overhead contamination. However, the majority of refrigerated food items frequently were not labeled or dated. In 6 of the 15 kitchens, large boxes were not stored 6 inches off the floor in dry storage areas. Frequently, observers noted that raw meats, seafood, and poultry were not stored below other refrigerated items.

Poor practices related to employee hygiene included inadequate handwashing, lack of hair restraints, and eating and drinking in food preparation areas. Inadequate handwashing was a problem frequently observed. Employee handwashing was not observed in 2 of the 15 school kitchens. In 13 of the 15 kitchens where employees were observed washing their hands, proper handwashing was a concern. In these instances, handwashing consisted of rinsing hands without soaping, inadequate scrubbing, and washing of hands in the food preparation sinks. Observers also reported a failure by employees to wear hair restraints. In 13 of the 15 kitchens, one or more employees were not wearing hair restraints. A third food safety abuse frequently observed was employees eating and drinking in food preparation areas. In almost half of the kitchens, food or drink was consumed in food preparation areas.

Additionally, there were several poor food-handling practices related to the cleaning and sanitation of utensils, equipment, and facilities. The most common poor practice was the failure to use test strips to check sanitizer concentration, a practice that was not observed during the audits in any of the 15 kitchens. The second most frequently observed problem was the inadequate cleaning and sanitizing of utensils and equipment. Sanitizing of manually washed dishes was performed infrequently and observed in only 3 of the 15 kitchens. Although dishes were cleaned, rinsed, and air-dried, they frequently were not sanitized. Cleaning and sanitizing of food contact surfaces was not observed in five of the kitchens. In 10 of the kitchens, cleaning and wiping, but not sanitizing, of food contact surfaces was observed.

These observations of several poor food-handling practices are consistent with food safety practices observed in other research studies (Brown et al., 1982; Gilmore et al., 1998; Kim & Shanklin, 1999; Raccach et al., 1985). The audit tool detected poor food-handling practices that could have a significant impact on the quality of food served.

Conclusions And Application

The purpose of this study was to develop and test an audit tool for use in school foodservice. The tool was easy to use and would be a practical way to conduct a quick assessment of food-handling practices. The tool was useful in detecting failure to adhere to known standards of food handling in the 15 kitchens observed.

Results from this study suggest that this audit tool could be useful for school foodservice directors or site managers in identifying poor employee food-handling practices that could become potential food safety problems. This tool can be used as is or adapted by school foodservice directors to conduct food safety self-inspections. In a fairly short time, the audit can provide school foodservice directors or site managers with a good sample of food-handling practices of employees. Results of such an audit would be useful for identifying areas that require additional training and where more supervision and employee feedback are needed to ensure that standard operating procedures are followed.

In order to ensure that safe food is served to our school children and that schools’ HACCP programs are being followed, the food-handling practices of school foodservice employees need to be monitored routinely. These audits could be conducted on an ongoing basis as part of monitoring compliance to food safety and HACCP programs. The audit form provides documentation of food-handling practices, and corrective action can be planned as a result.

Limitations

There were limitations in conducting this study. First, the audits were conducted in only one region of the country; therefore, the results cannot be generalized to school foodservice programs nationwide. While the tool contains many recognized standards for safe food handling, adaptations may be necessary to focus on areas of particular importance in a school district.

Second, three observers were conducting the audits. Although training had been conducted and inter-rater reliability determined, discrepancies in interpreting food-handling practices may have occurred among the observers. Perhaps the tool could include criteria related to the practices that would improve reliability among observers. Third, single audits were conducted for approximately two hours during a similar period in each of the school foodservice operations.

The audit tool may need to be tested during other time periods and for varying lengths of time. Similarly, food-handling practices may differ from day to day and among individual employees. Repeated uses of the tool would reveal to managers a consistent picture of employees’ behaviors and may be an appropriate routine strategy for monitoring.

Several significant poor food-handling practices were observed during the audits providing an overall profile of employee food safety behaviors. These audits provided a basis for determining food-handling practices occurring in these operations and indicated areas requiring attention.

It is recommended that audits be conducted in other regions of the country to refine the audit tool and to determine if findings in this study are consistent with operations around the country. Also, research needs to be conducted to determine school foodservice employees’ attitudes toward food safety; they could provide a means of understanding why some employees do not follow food safety practices consistently.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the California Dietetic Association for the Zellmer Grant award, which made funding for the project possible. The authors also acknowledge and thank the Bay Area school foodservice directors whose support made this research possible.

References

American School Food Service Association. (1999). About ASFSA [Online]. Available: www.asfsa.org/about

Brown, N.E., McKinley, M.M., Aryan, K.L., & Hotzler, B.L. (1982). Conditions, procedures, and practices affecting safety of food in 10 school foodservice systems with satellites.School Food Service Research Review, 6, 36-41.

Byran, F.L. (1982). Diseases transmitted by foods. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

California Association of Environmental Health Administrators. (2000). California Uniform Retail Food Facilities Law (CURFFL). Sacramento, CA: California Association of Environmental Health Administrators.

Cary, A. (2001, February 18). $4.75 million awarded in E.coli case [Online]. Available: www.tri-cityherald.com/news/2001/0217/story1.html

The National Restaurant Association Educational Foundation.

(1999). ServSafe® Coursebook. Chicago: The Educational Foundation of the National Restaurant Association.

Food and Drug Administration. (1999). Food Code 1999. Springfield, VA: National Technical Information Service. [Online]. Available: www.cfsan.fda.gov/~dms/foodcode.html

General Accounting Office. (2000). School meal programs. Few outbreaks of foodborne illness reported [Online]. Available:http://schoolmeals.nal.usda.gov:8001/safety/GAORC053.pdf

Gilmore, S.A., Brown, N.E., & Dana, J.T. (1998). A food quality model for school foodservices. The Journal of Child Nutrition & Management, 22, 33-39.

Kim, T., & Shanklin, C.W. (1999). Time and temperature analysis of a school lunch meal prepared in a commissary with conventional versus cook-chill systems. Foodservice Research International, 11, 237-249.

Neumann, R. (1998). The eight most frequent causes of foodborne illness. Food Management, 33 (6), 28.

Raccach, M., Morrison, M.R., & Farrier, C.E. (1985). The school food service operation: An analysis of health hazards. Dairy and Food Sanitation, 5 (11), 420-426.

Reed, G.H. (1993). Safe food handling of potentially hazardous foods (PHF)–A checklist. Dairy, Food, and Environmental Sanitation, 13, 208-209.

Richards, M.S., Rittman, M., Gilbert, T.T., Opal, S.M., DeBuono, B.A., Neill, R.J., & Gemski,

- (1993). Investigation of a staphylococcal food poisoning outbreak in a centralized school lunch program. Public Health Reports, 108, 765-771.

Roefs, V.I. (2000). Catching up on food safety. Poppyseeds, 44 (2), 12-14.

U.S. Department of Agriculture. (2001). Child nutrition programs [Online]. Available: www.fns.usda.gov/cnd/Lunch/AboutLunch/faqs.htm

Biography

Joan Giampaoli is assistant professor, Department of Nutrition and Food Science, San Jose State University, San Jose, CA. Mary Cluskey is assistant professor, Department of Nutrition and Food Management, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR. Jeannie Sneed is associate professor, Hotel, Restaurant, and Institution Management, Iowa State University, Ames, IA.